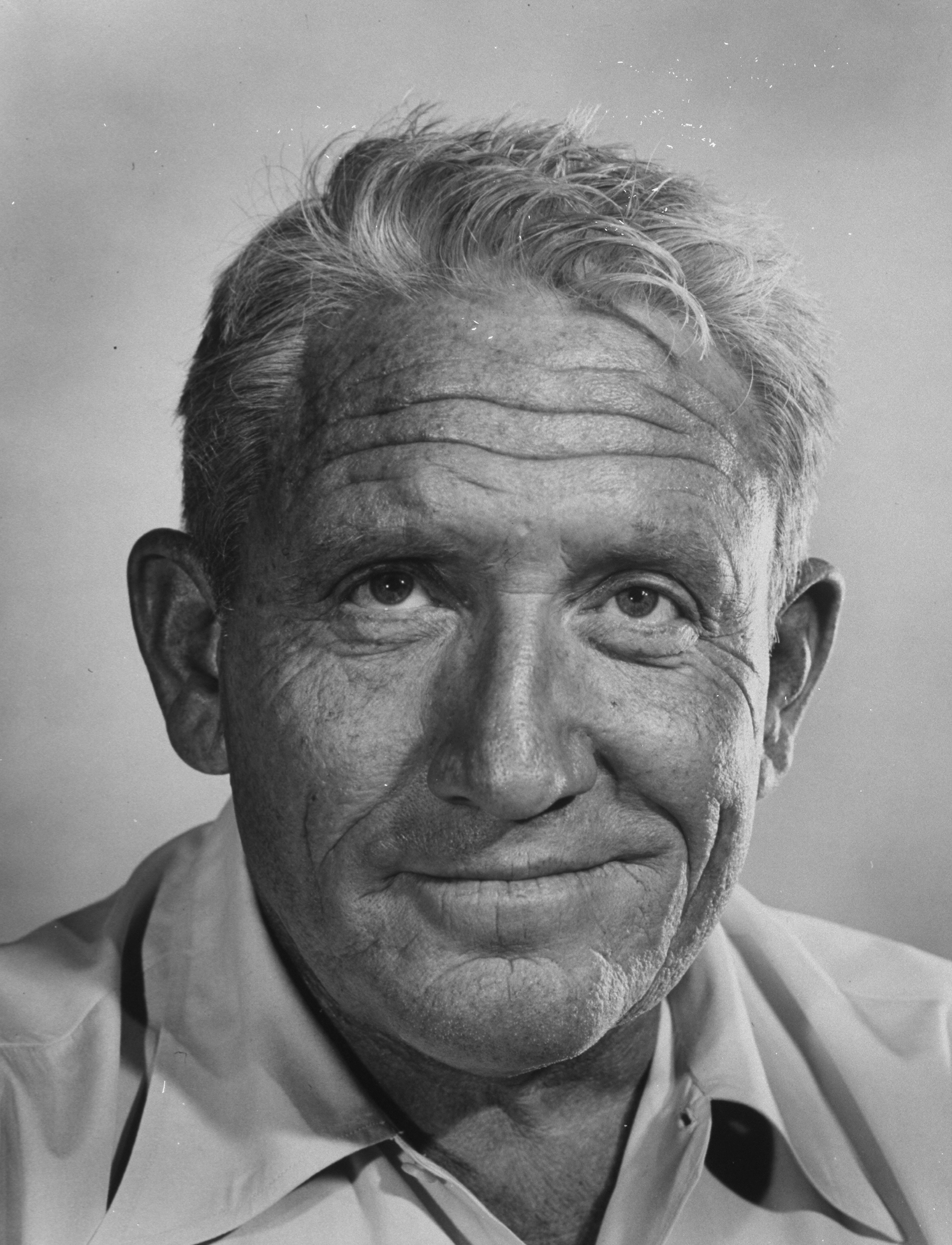

The notion of a celebrated, groundbreaking photographer being born in a photo studio owned and operated by his parents sounds like something out of an absurdist novel. But that’s exactly how and where LIFE’s J.R. Eyerman (“J” to friends and colleagues), who made some of the most recognizable and most frequently reproduced pictures of the 20th century, came into the world.

In an informal biography that he sent to LIFE magazine in 1940, before he was made a staff photographer, Eyerman wrote revealingly and self-deprecatingly of himself:

Full name is J.R. Wharton Eyerman. I was born in what was “the oldest and largest photographic studio in [Montana]”. . . . My parents took advantage of the town’s leading citizen to the extent of giving me his full name. The initials didn’t stand for anything. . . .

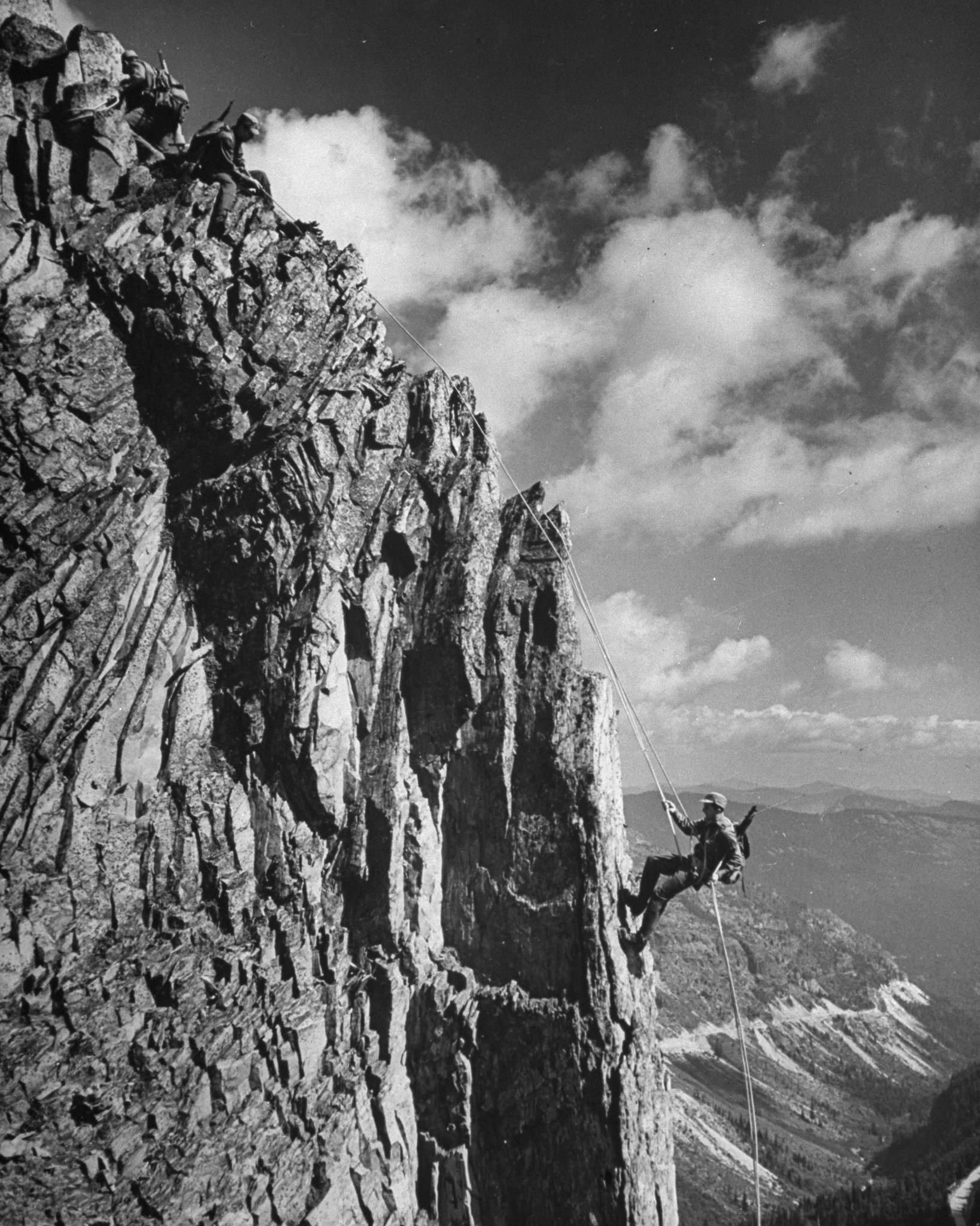

I learned photography from my mother, a beautiful photographer. My father let me follow him on out-of-door work and as a lad I helped him make thousands of negatives in Yellowstone and Glacier Park. I left Butte and photography at the age of 15 for the University of Washington at Seattle. Four years later I was a civil engineer doing structural design. . . .

My biggest assignment to date is for 300 8×10 Kodachromes of the Northwest — it has me worried, because there is so little good light in the summer. My favorite kind of work is photographing these N.W. natives the way they are — Indians, loggers, small-town newspaper men, mill hunkies, fishermen. They’re swell people.

In 1943, at the heigh of the Second World War, Eyerman was accredited to the Atlantic fleet. He covered naval operations during the North African and Sicilian campaigns — and, according to notes in LIFE’s archives, “had his watch, two cameras and foot broken during a near-miss during the landing at Gela.” A year later, he was in the Pacific for a long assignment during the Marianas campaign, and in 1944 covered the first aircraft carrier strike on Manila.

That Eyerman had a gift for getting along with people, like his “swell” subjects in the American Northwest, is evident in another note in the LIFE archives: a 1945 office memorandum discussing his reputation among the sailors with whom he spent so much time. “Eyerman is a very wonderful person,” the memo reads, quoting an acquaintance who knew him in the Pacific. “People out forward, from the admirals on down, appear to have more real respect for J. than for almost any other correspondent, and I think TIME Inc. is fortunate to have him on our side.”

Throughout his career, meanwhile, Eyerman’s engineering skills, and his passion for finding a way to take the “untakeable” picture, kept him busy not only behind the camera, but inside it, as well.

In the 1957 book, LIFE Photographers: Their Careers and Favorite Pictures, author Stanley Rayfield notes that “Eyerman’s technical innovations have helped push back the frontiers of photography. He perfected an electric eye mechanism to trip the shutters of nine cameras to make pictures of an atomic blast; devised a special camera for taking pictures 3600 feet beneath the surface of the ocean; successfully ‘speeded up’ color film to make previously impossible color pictures of the shimmering, changing forms and patterns of the aurora borealis.”

In other words, when a new device or technique was called for, Eyerman frequently came up with a solution using his own head and hands. Like so many of LIFE’s photographers, he was by nature a tinkerer: he liked figuring out how things worked and, if possible, making them work a little better.

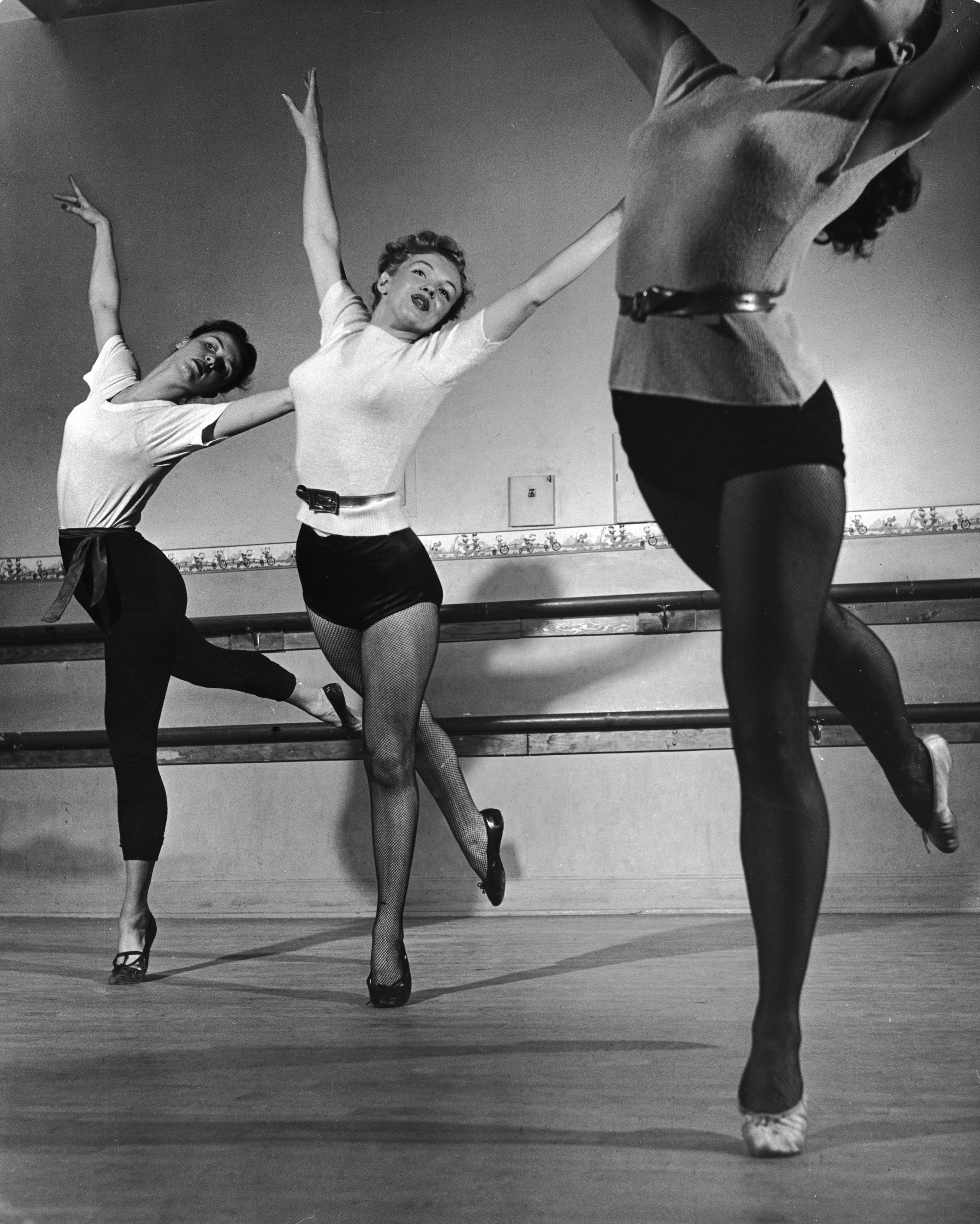

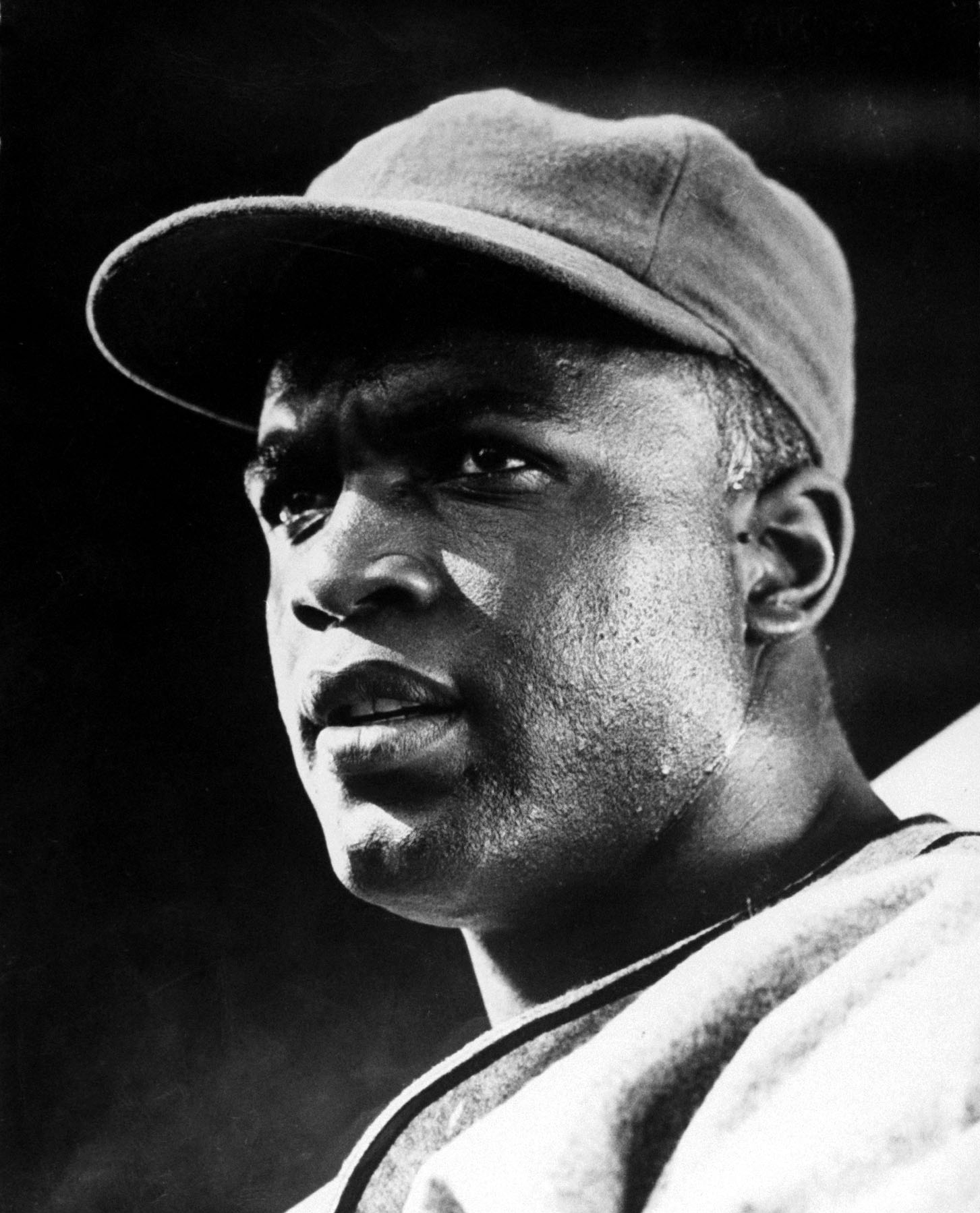

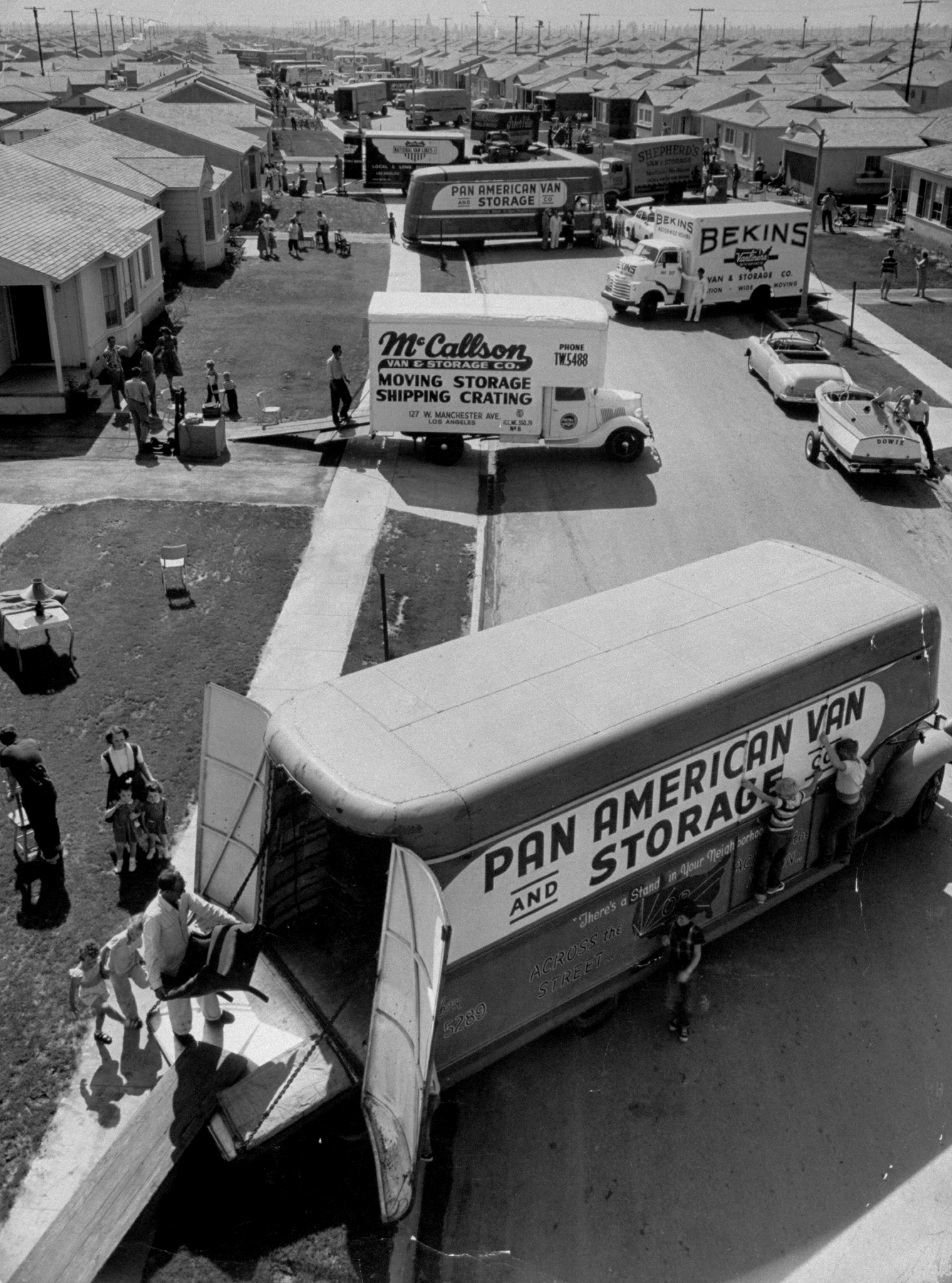

Here, LIFE.com pays tribute to Eyerman’s long career with pictures that, we hope, at least hint at the man’s dizzying versatility, talent and technical prowess.

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter at @LizabethRonk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com