Some photographers are so skilled at covering a specific topic, or through the years have created so distinctive a feel in their pictures, that it’s possible to encounter an image—even an image one has never seen before—and say with something like certainty, “That’s a Leifer” or “That’s a Halsman” or “That’s a Nachtwey.” Familiarity with a recognizable style, meanwhile, hardly breeds contempt; a master can find countless ways to keep his or her vision fresh—even if the subject matter or the visual vocabulary remains relatively constant across decades.

Andreas Feininger might photograph the Brooklyn Bridge a hundred times, but his artistry and technical virtuosity makes it new each and every time.

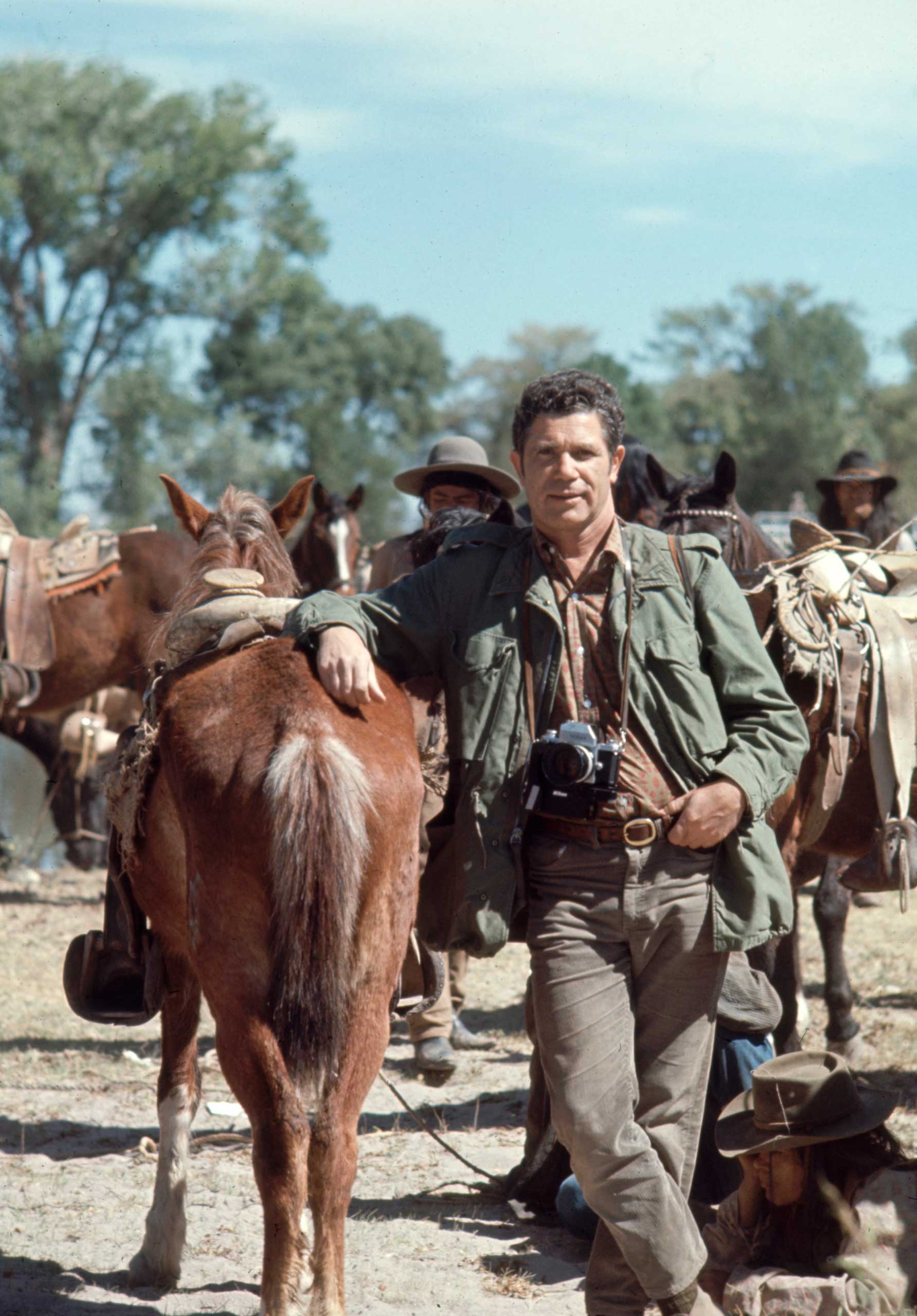

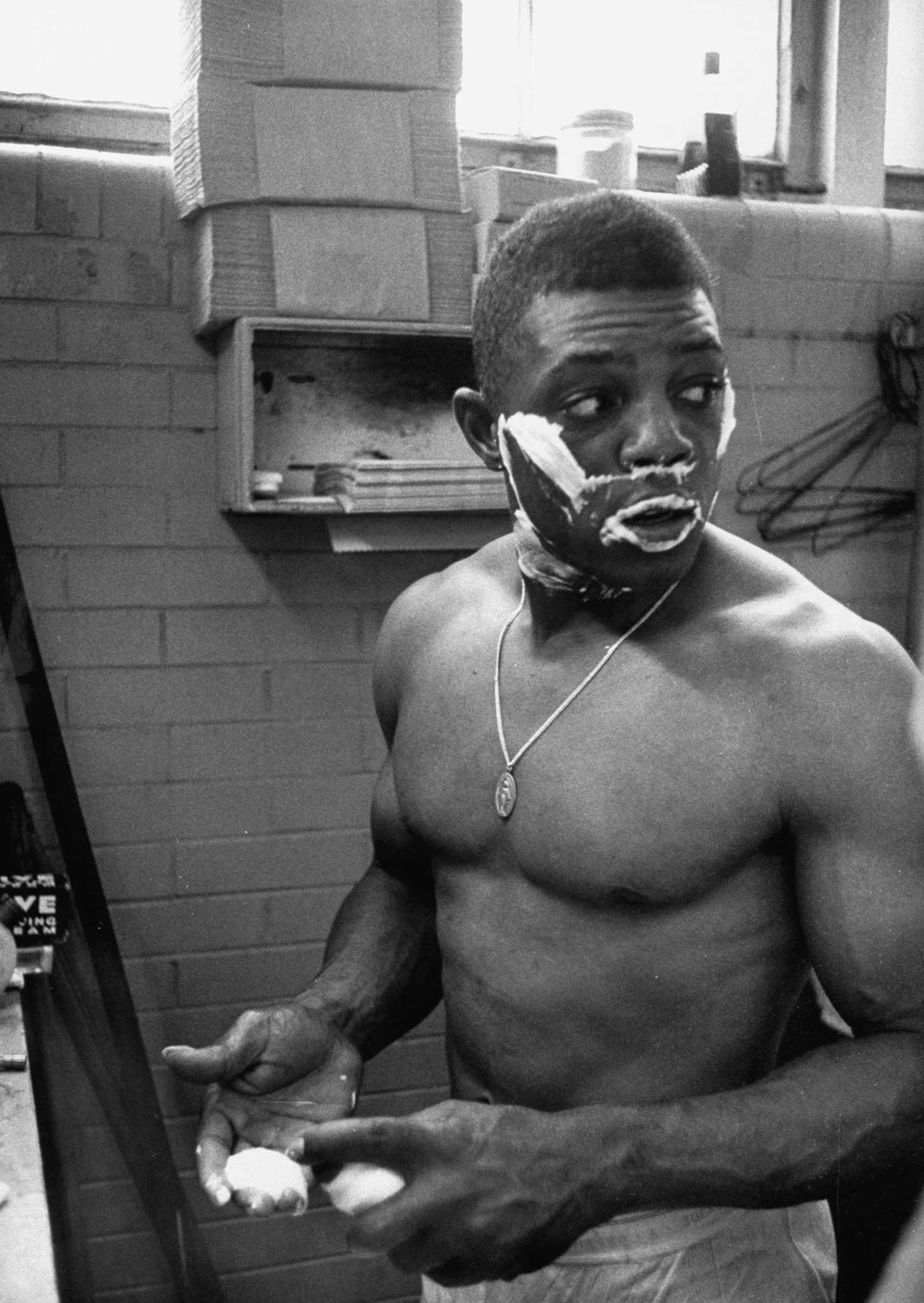

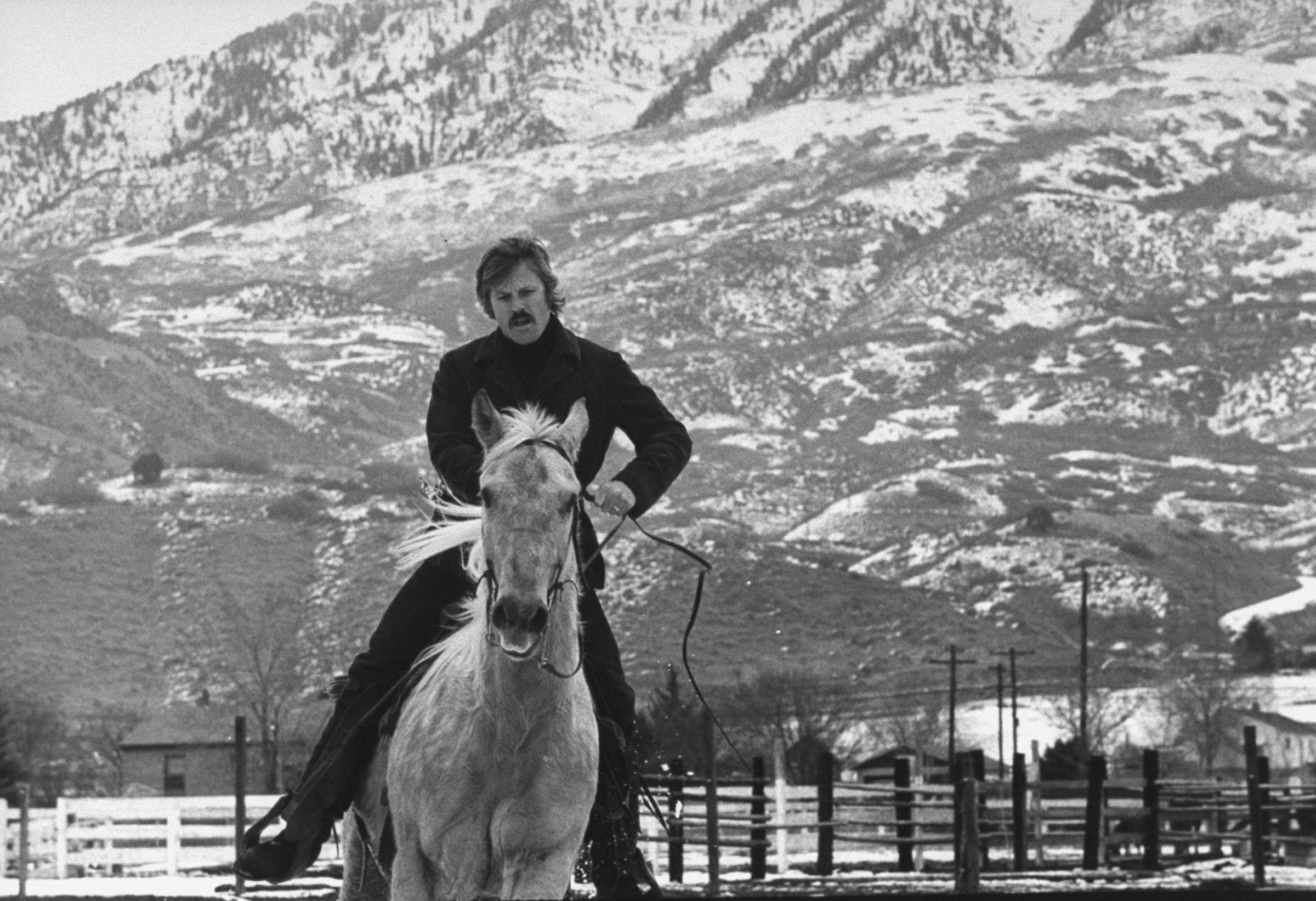

Then there are great photographers whose work is so phenomenally varied—a uniform, unbroken excellence the only common thread running throughout—that every new shot one encounters might have been made by a different individual. John Dominis is such a photographer, and the photos presented here serve as a testament to the man’s enviable ability to see and to capture anything.

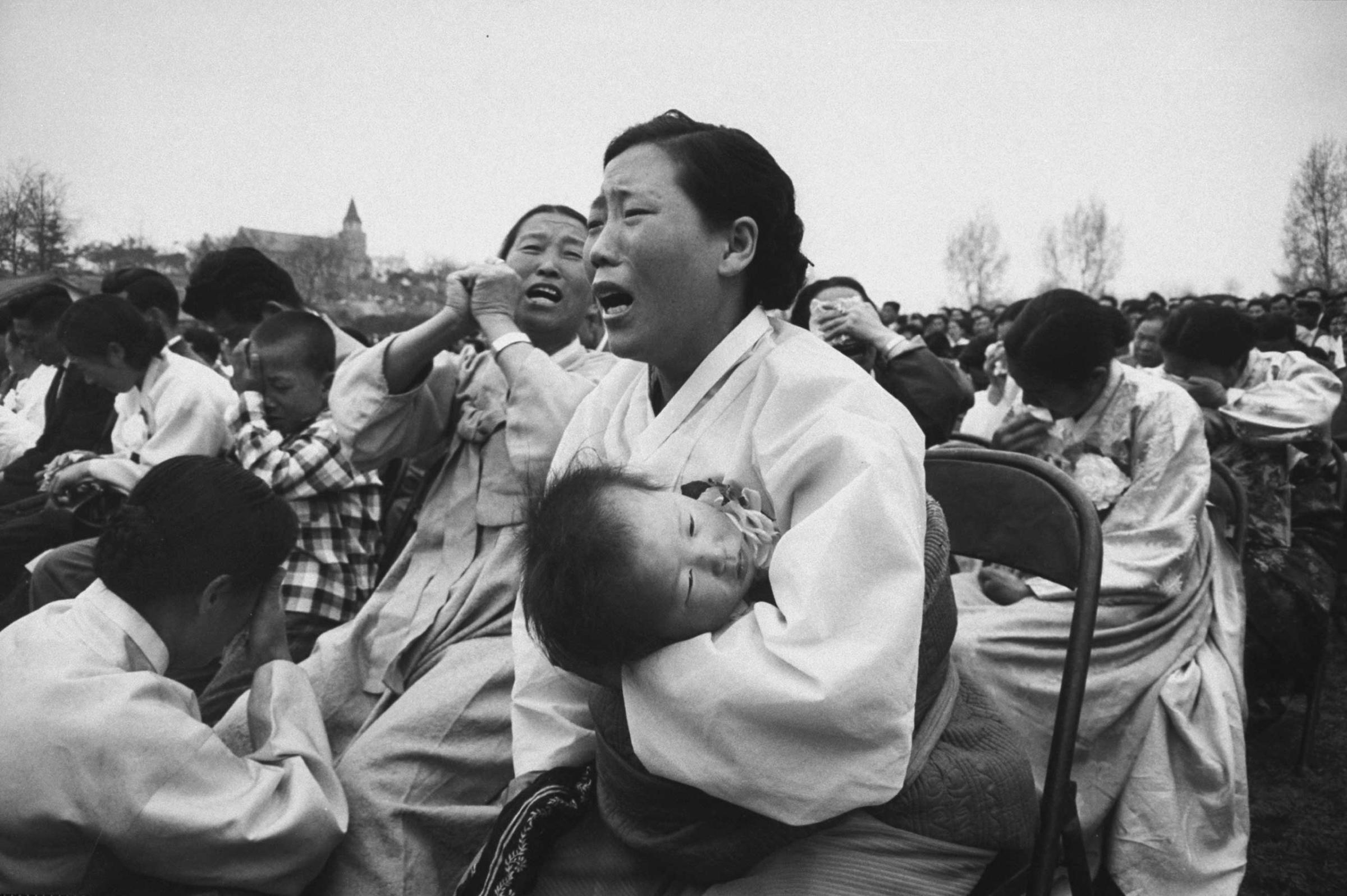

Born in Los Angeles in 1921, Dominis was majoring in cinematography at USC when he left school in 1943 to enlist in the Air Force. After the war, he freelanced as a photographer for a number of national publications, including LIFE, and was put on staff in 1950 when he volunteered to cover the Korean War.

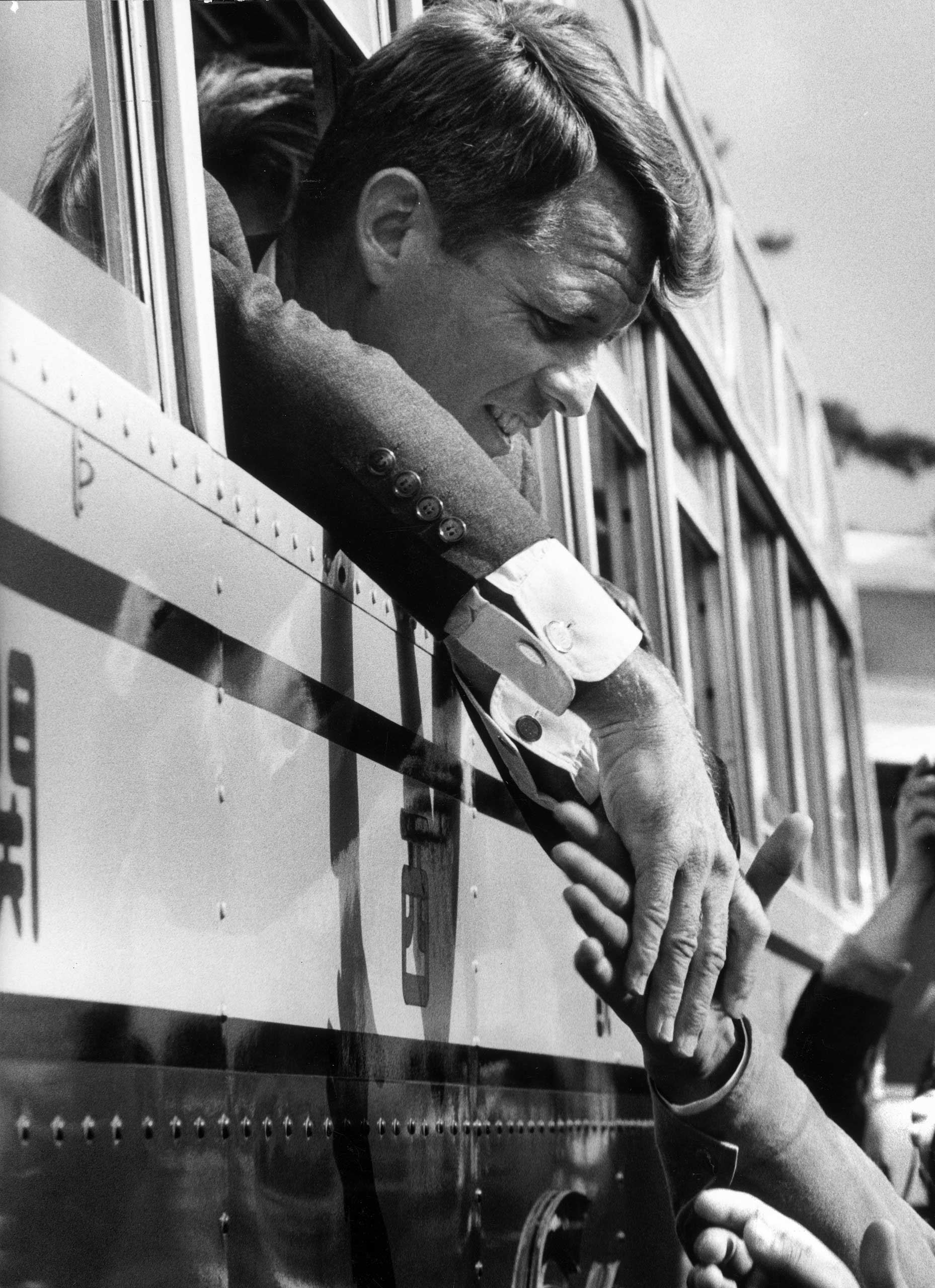

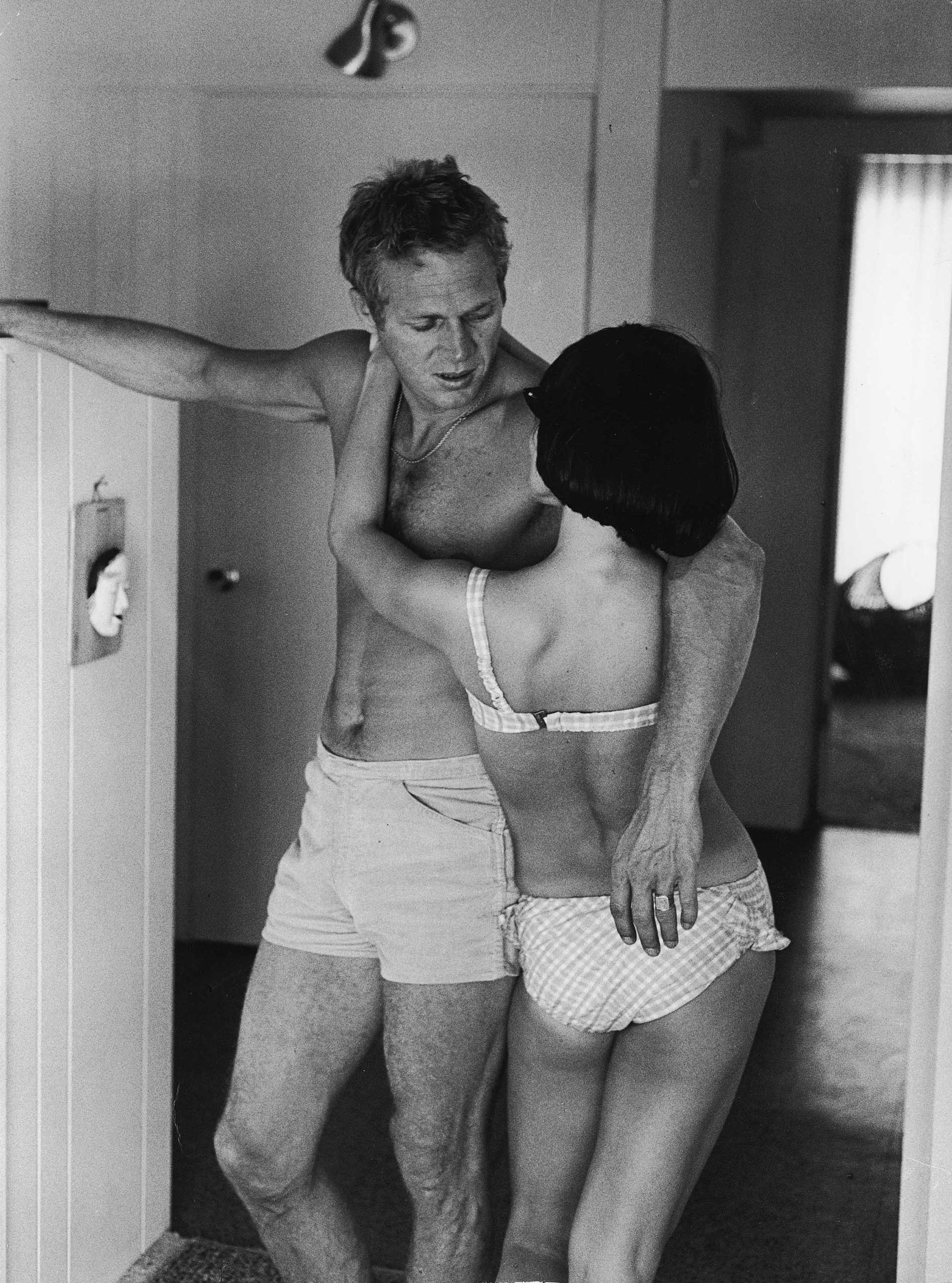

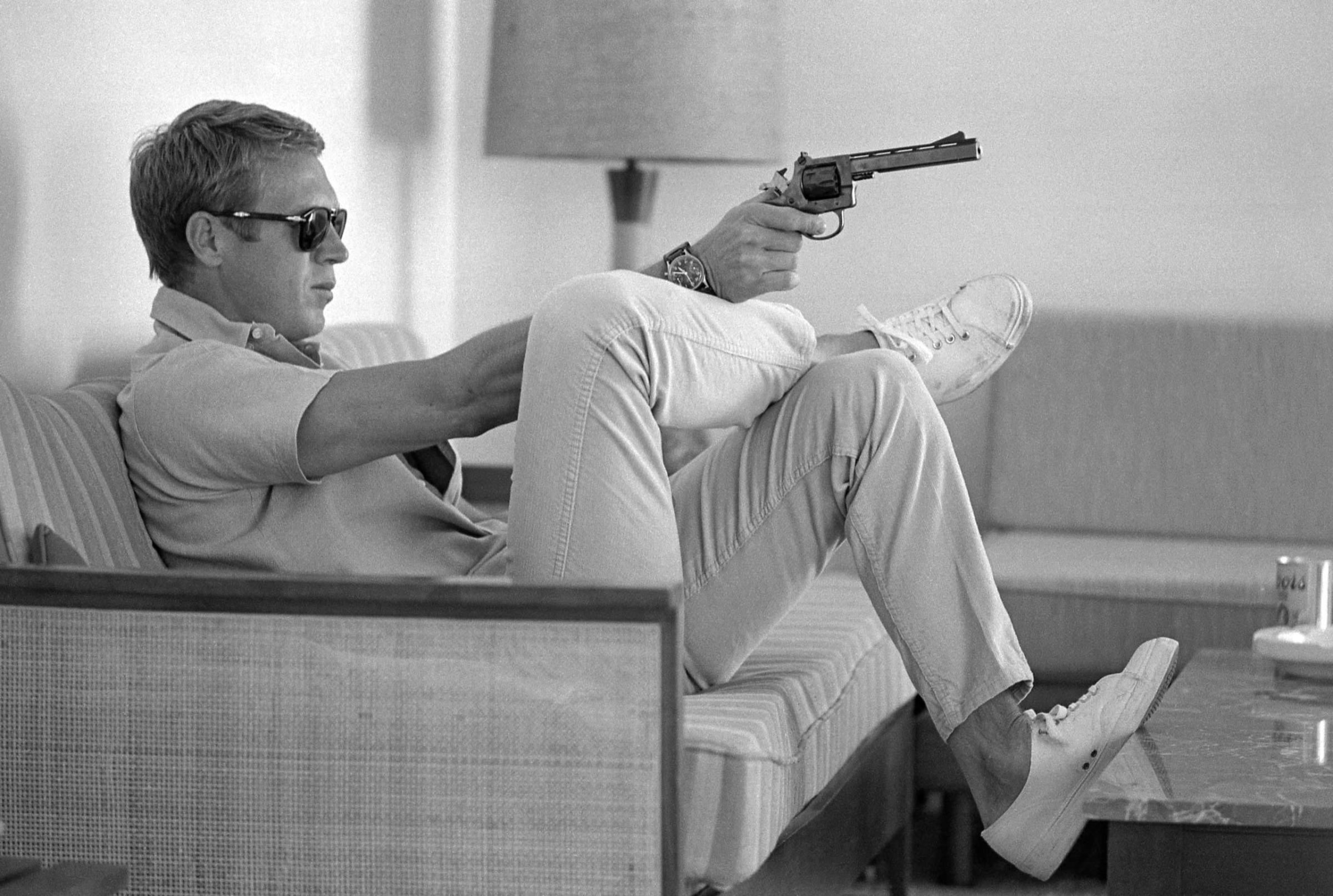

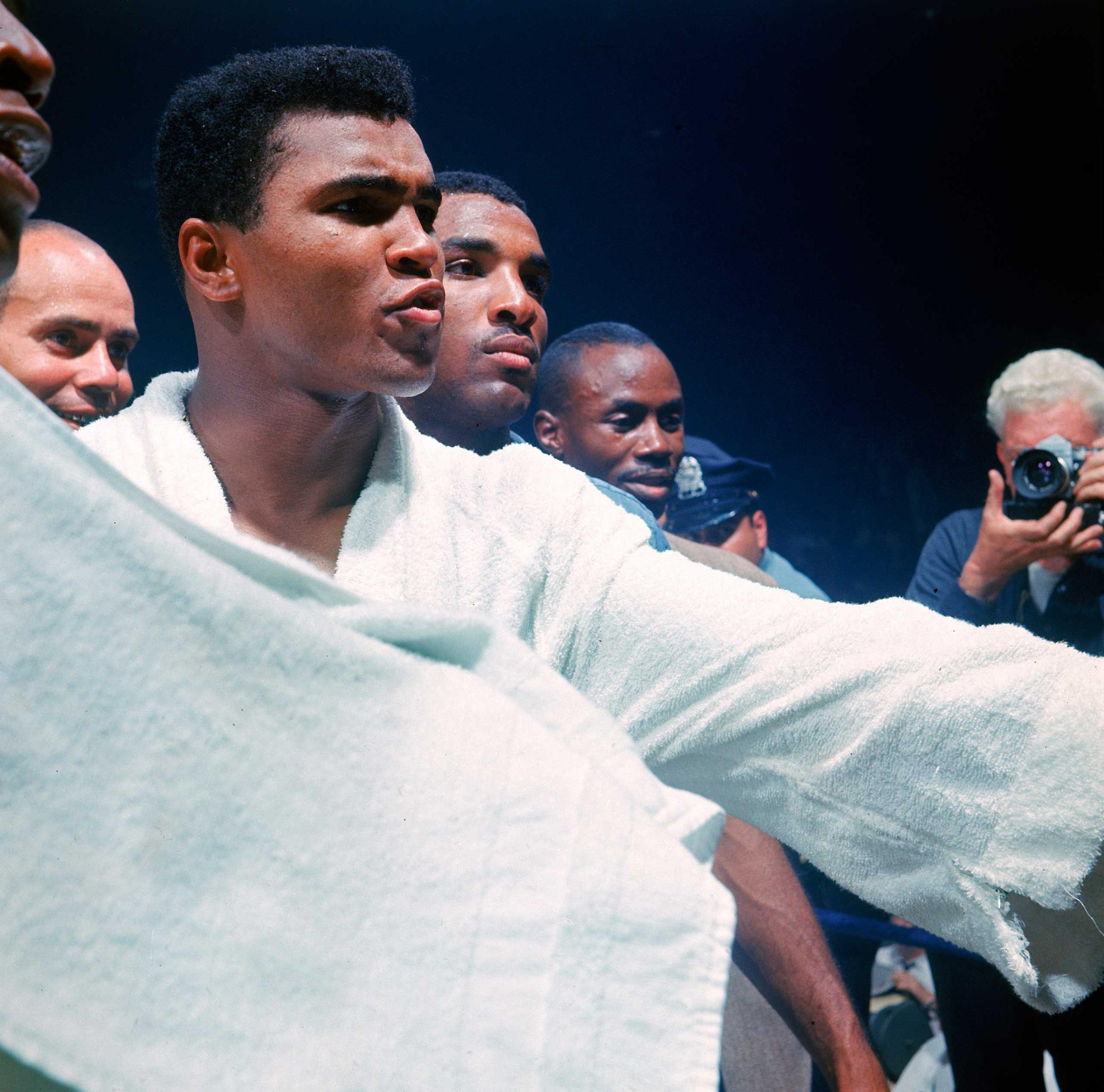

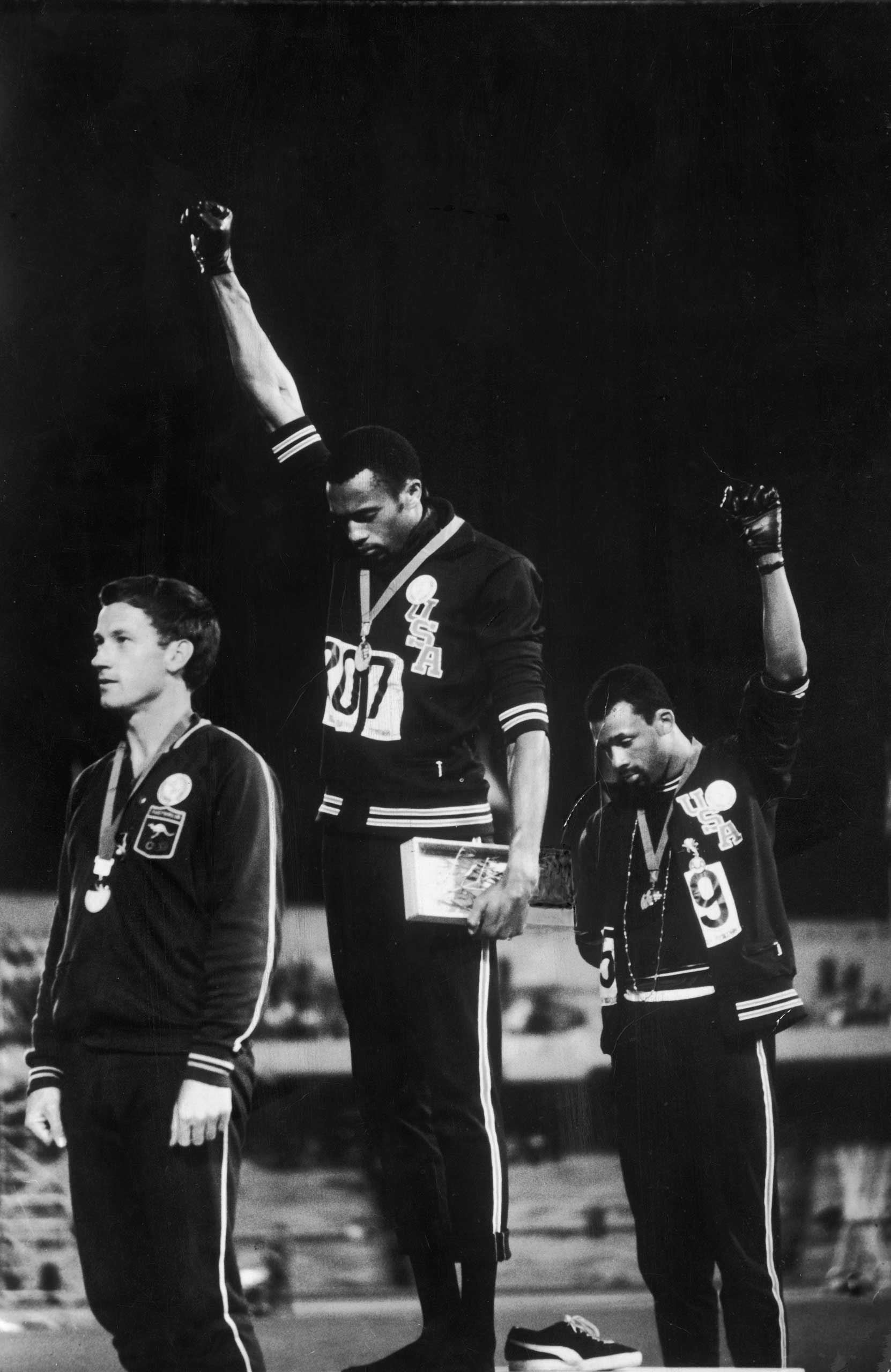

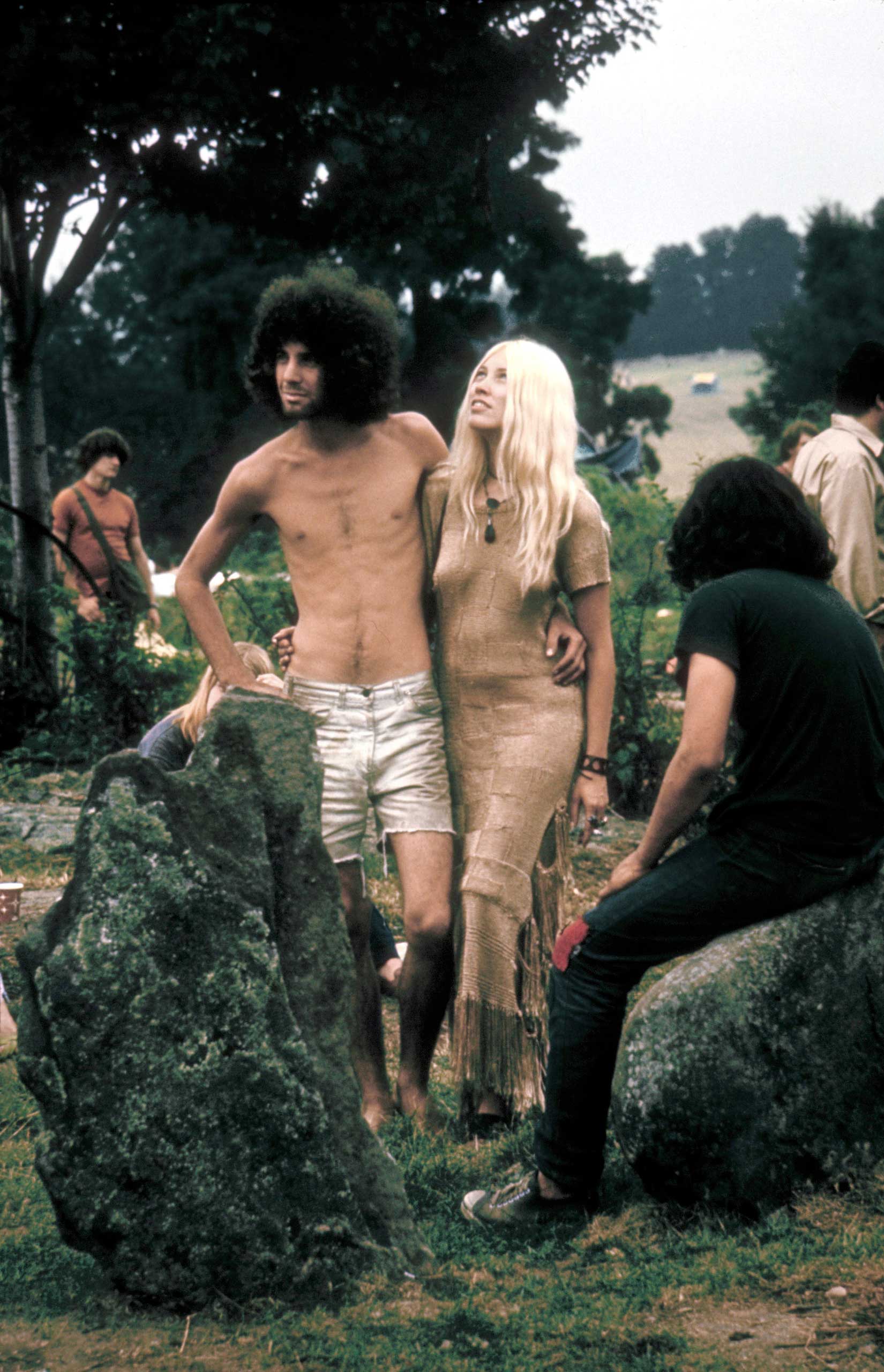

Over the next two-plus decades, he traveled the globe, working in Southeast Asia and the American Southwest, Africa and Europe, Mexico and New York City. He covered six Olympics, including the 1968 Summer Games in Mexico City, where he made his famous picture of American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos on the podium, their gloved fists raised in a Black Power salute (slide 26 here). He was one of the first LIFE photographers to report from Vietnam. He covered Woodstock. He created what many consider the definitive photo essays on pop culture icons like Frank Sinatra and Steve McQueen. He photographed big cats (lions, leopards, cheetahs) in Africa and he photographed the three Kennedy brothers—John, Robert and Edward—separately, early in their careers.

His 1965 photograph of Mickey Mantle tossing his helmet in disgust after a terrible at-bat is one of the most eloquent pictures ever made of a great athlete in decline and—just to keep everyone guessing—John Dominis also made some of the most memorable images of food ever to grace the pages of LIFE.

“The great thing about working with LIFE,” Dominis once said, “was that I was given all the support and money and time, whatever was required, to do almost any kind of work I wanted to do, anywhere in the world. It was like having a grant, a Guggenheim grant, but permanently.”

Dominis has been remarkably candid about his work, and no more so than when discussing how he managed to make one of the most famous, and controversial, shots of his career: the bristling-with-energy picture of a leopard and a baboon (slide 25) facing off in what one immediately imagines—rightly, as it turns out—is a fight to the death.

In John Loengard’s terrific 1998 book, LIFE Photographers: What They Saw, Dominis says of that photo:

I certainly wasn’t a cat expert, but I could hire people who knew things. They’d lined up a hunter in Botswana, who was a hunter for zoos. He had caught a leopard, and he put the leopard in the back of the truck, and we went out into the desert. He would release the leopard, and most of the time the leopard would chase the baboons and they would run off and climb trees. I had photographed all this. But for some reason one baboon . . . turned and faced the leopard, and the leopard killed it. We didn’t know that this was going to happen. I just turned on the camera motor, and I got this terrific shot of this confrontation.

There was a different feeling about that in the 1960s. We were always setting up pictures. . . . But now there are many, many more competent photographers doing this stuff over long periods of time—four or five years if a scientist is on a big study. . . . No one was working that way then. I felt that my job was to get the pictures. . . . We shot a gazelle and put it in a tree and waited for a cat to come. I didn’t feel bad about it at all. It sounds terrible now, I know, and maybe my attitude would be different now. . . . I’ve been criticized a lot. But to me, I had to do what I did.

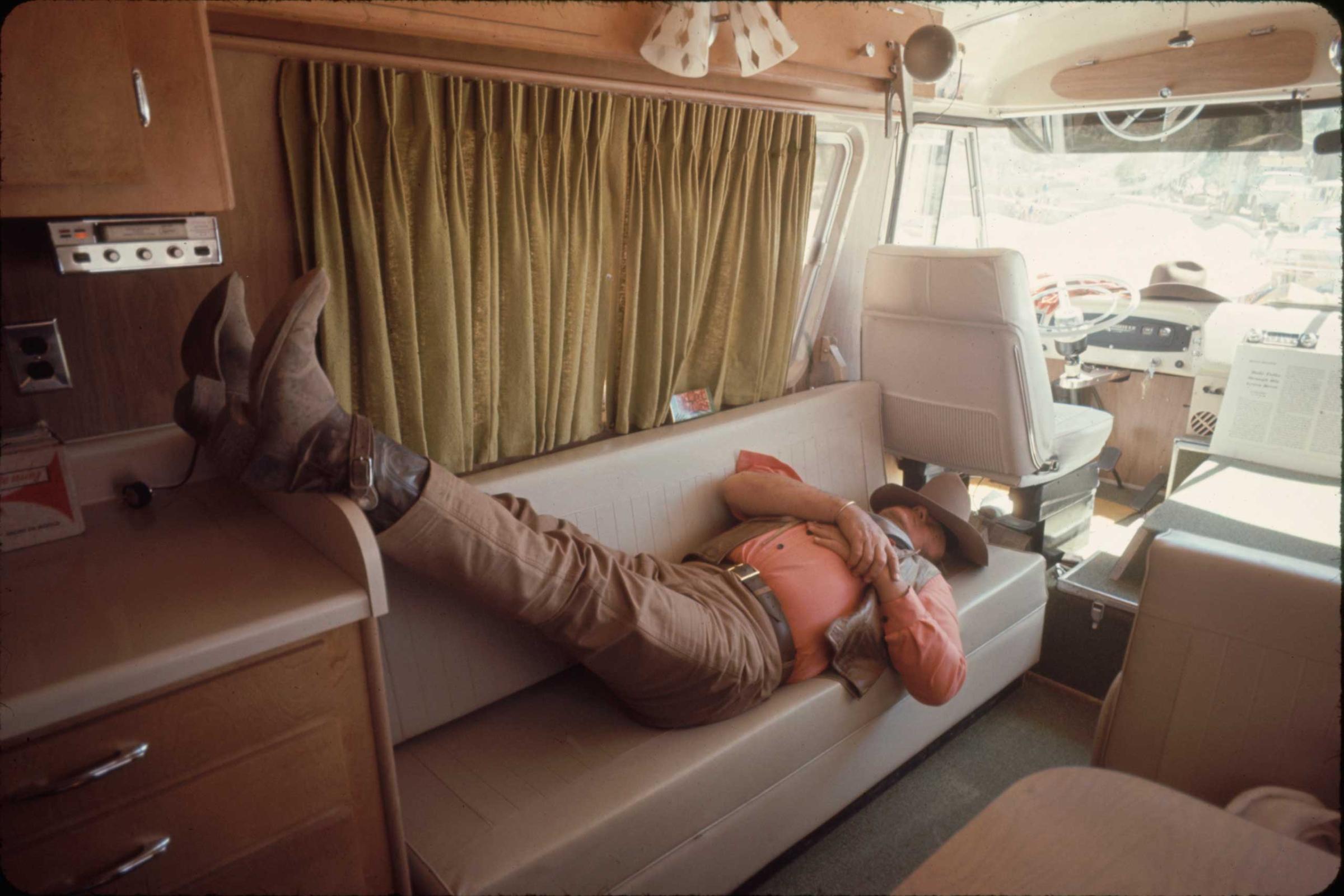

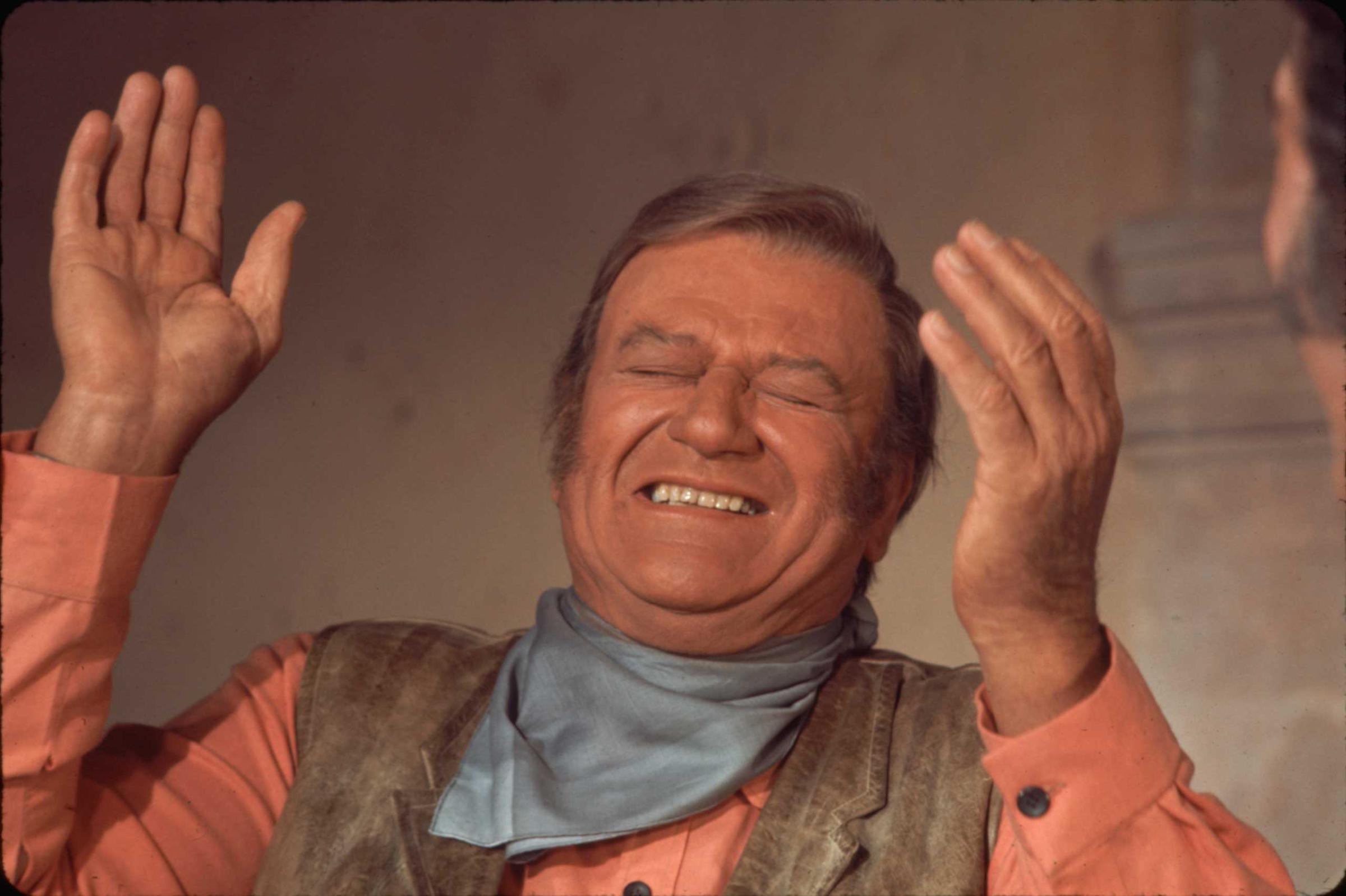

His encounters with humans were (usually) less fraught, but always involved the same degree of preparation. Of his remarkable series of photos of Steve McQueen, and how he got the notoriously private and solitary actor to relax with a photographer around, Dominis told LIFE.com:

When I was living in Hong Kong I had a sports car and I raced it. And I knew that McQueen had a racing car. I rented one anticipating that we might do something with them. He was in a motorcycle race out in the desert, so I went out there in my car and met him, and I say, ‘You wanna try my car?’ We went pretty fast—I mean, as fast as you can safely go without getting arrested—and we’d ride and then stop and trade cars. He liked that, and I knew he liked it. I guess that was the first thing that softened him.

Then there’s Woodstock, an event that opened the eyes of a man who’d seen everything:

“I really had a great time,” Dominis told LIFE.com, decades after the fact. “I was much older than those kids, but I felt like I was their age. They smiled at me, offered me pot. . . . You didn’t expect to see a bunch of kids so nice; you’d think they’d be uninviting to an older person. But no—they were just great!

“I worked at LIFE for 25 years, and worked everywhere and saw everything, and I’ve told people every year since the Woodstock festival that it was one of the greatest events I ever covered.”

Dominis became photo editor of People magazine in the mid-1970s and was an editor at Sports Illustrated for a few years, as well (1978 – 1982). But it was his work for LIFE in the 1950s, ’60s and into the early ’70s that not only defined his peripatetic career, but produced some of the most memorable and moving images of the 20th century.

[NOTE: John Dominis died on Monday, Dec. 30, 2013, at his home in New York City. Dominis was 92 years old. Farewell, John. We won’t see your like again.]

Ben Cosgrove is the Editor of LIFE.com

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter at @LizabethRonk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com