As Emmanuel Macron emerged from the Louvre on Sunday night, to greet thousands of his supporters, a sea of blue, white and red flags welcomed France’s new president. Moving in unison, these colors brought to life France’s motto of liberty, equality and fraternity — and, as photographer Christopher Anderson tells TIME, the prevalence of the flag reinforced for Macron’s supporters the sentiment behind a national symbol that many of them may have worried had been co-opted by the far right.

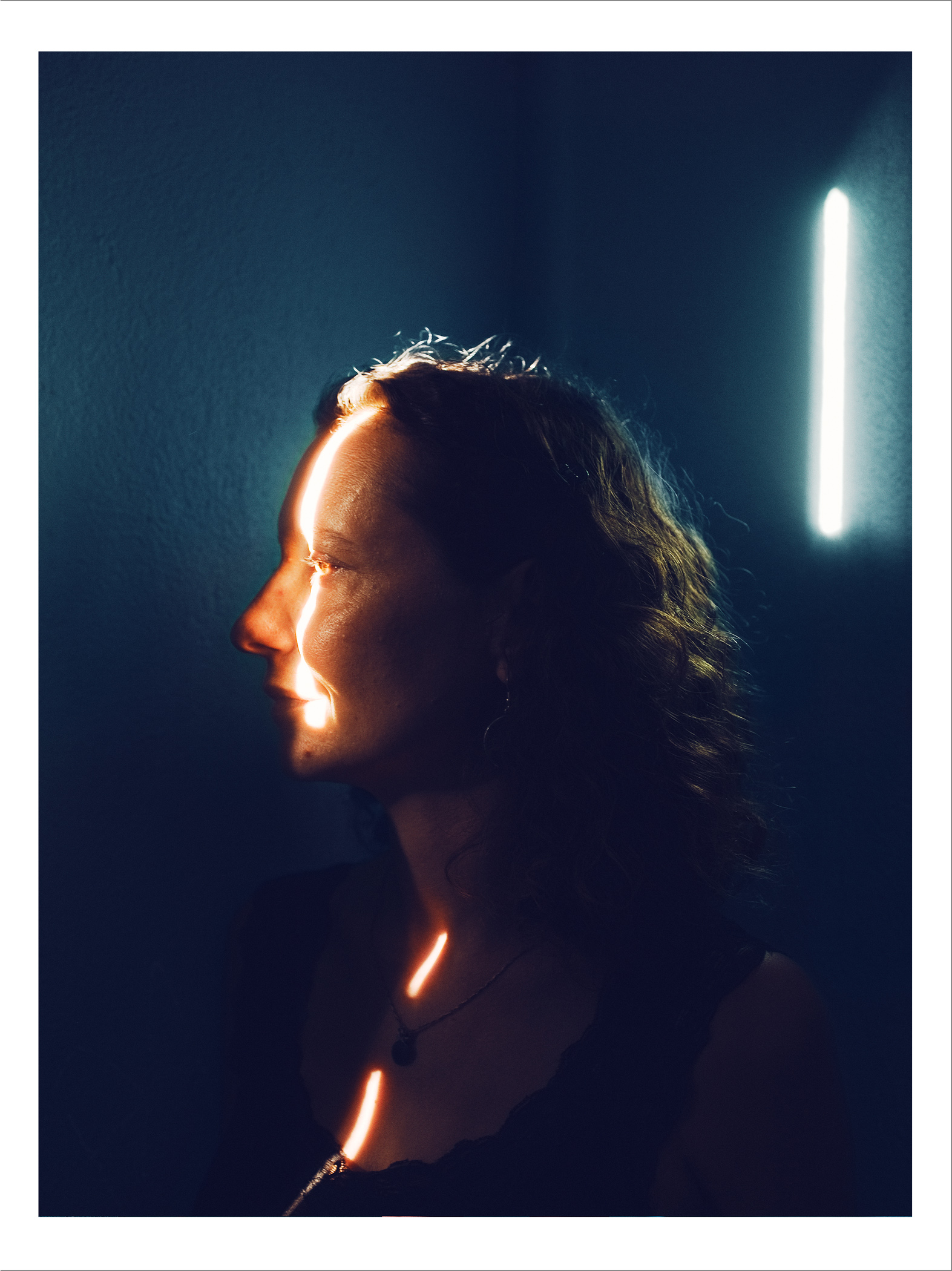

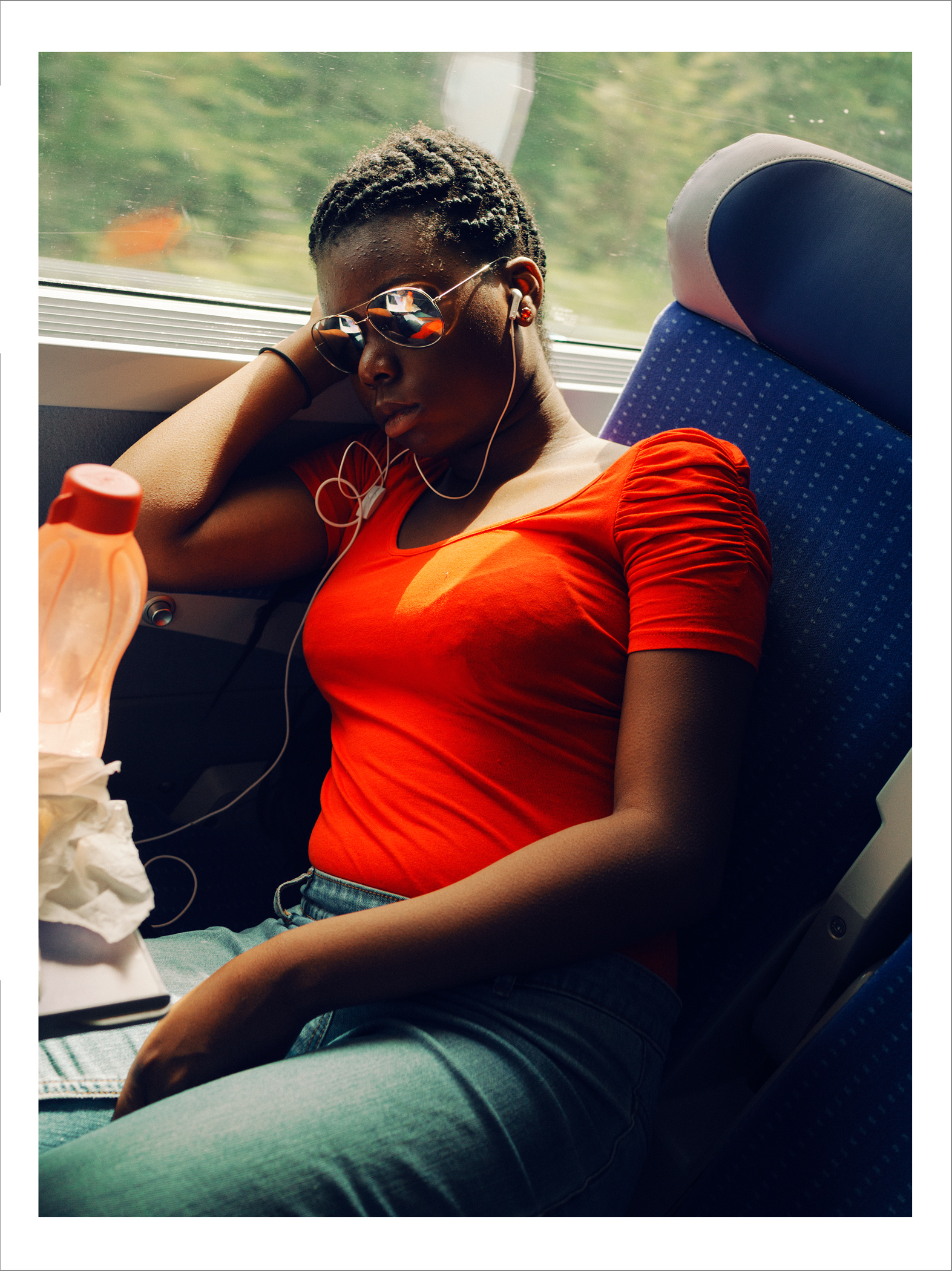

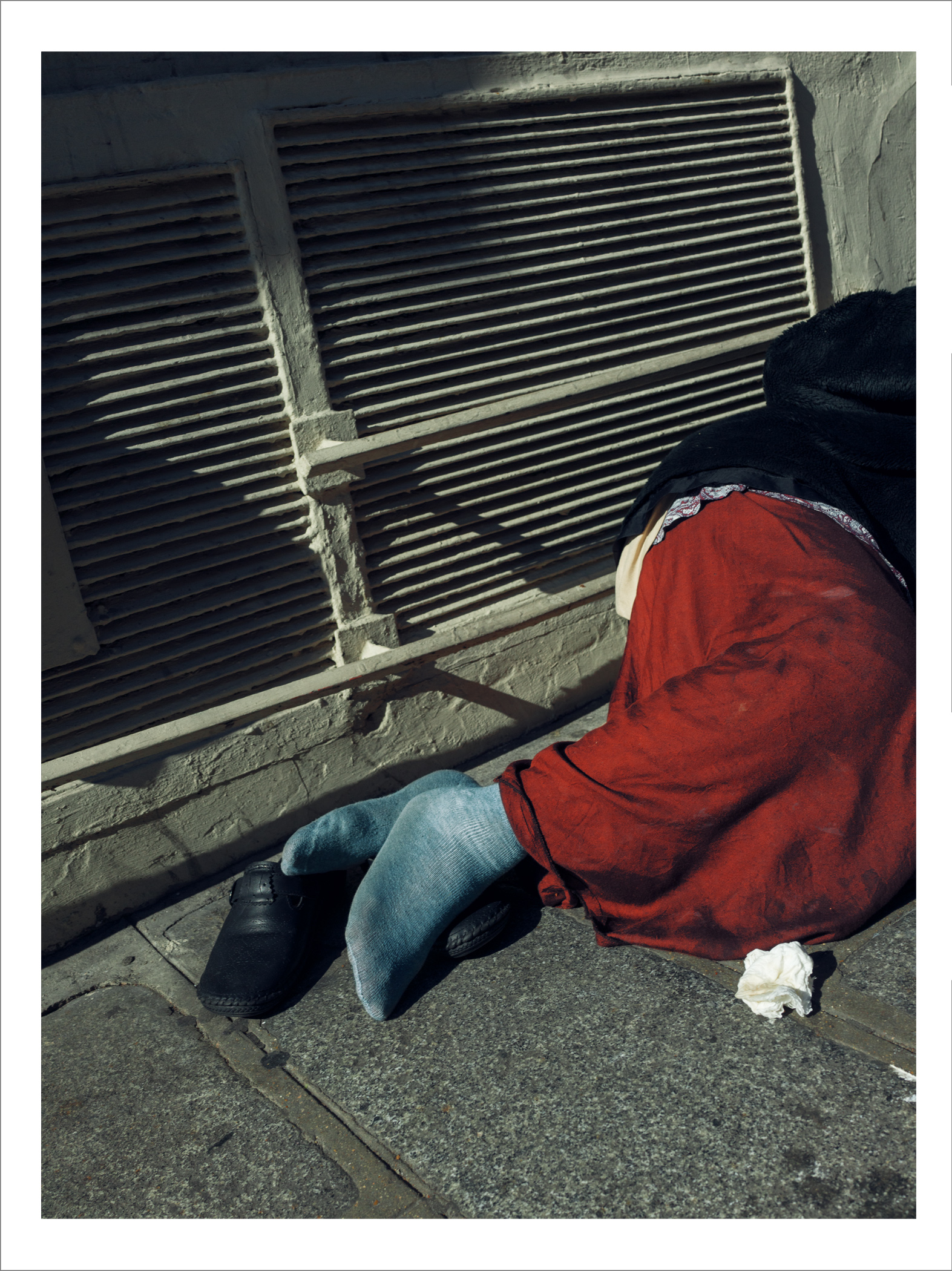

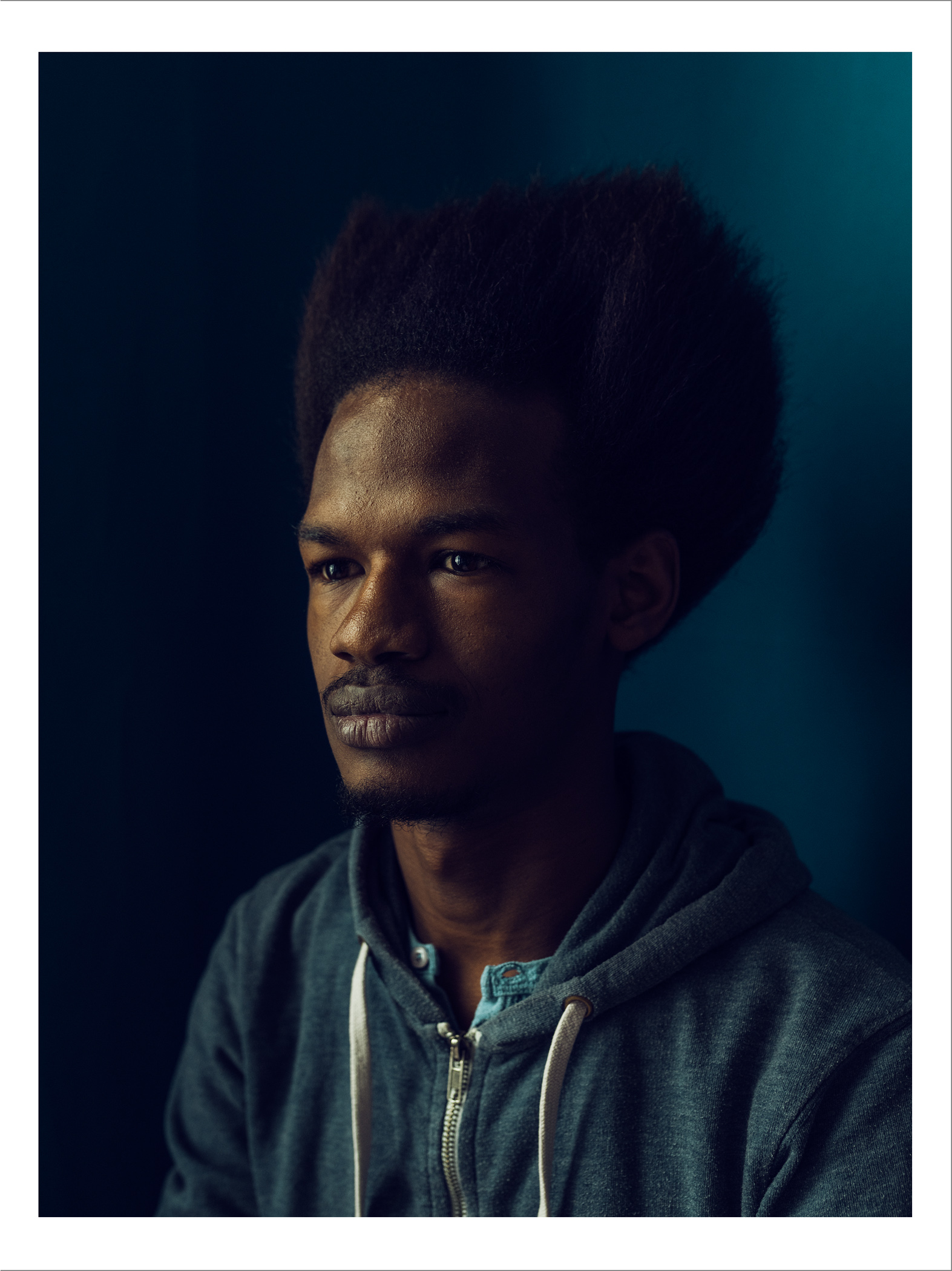

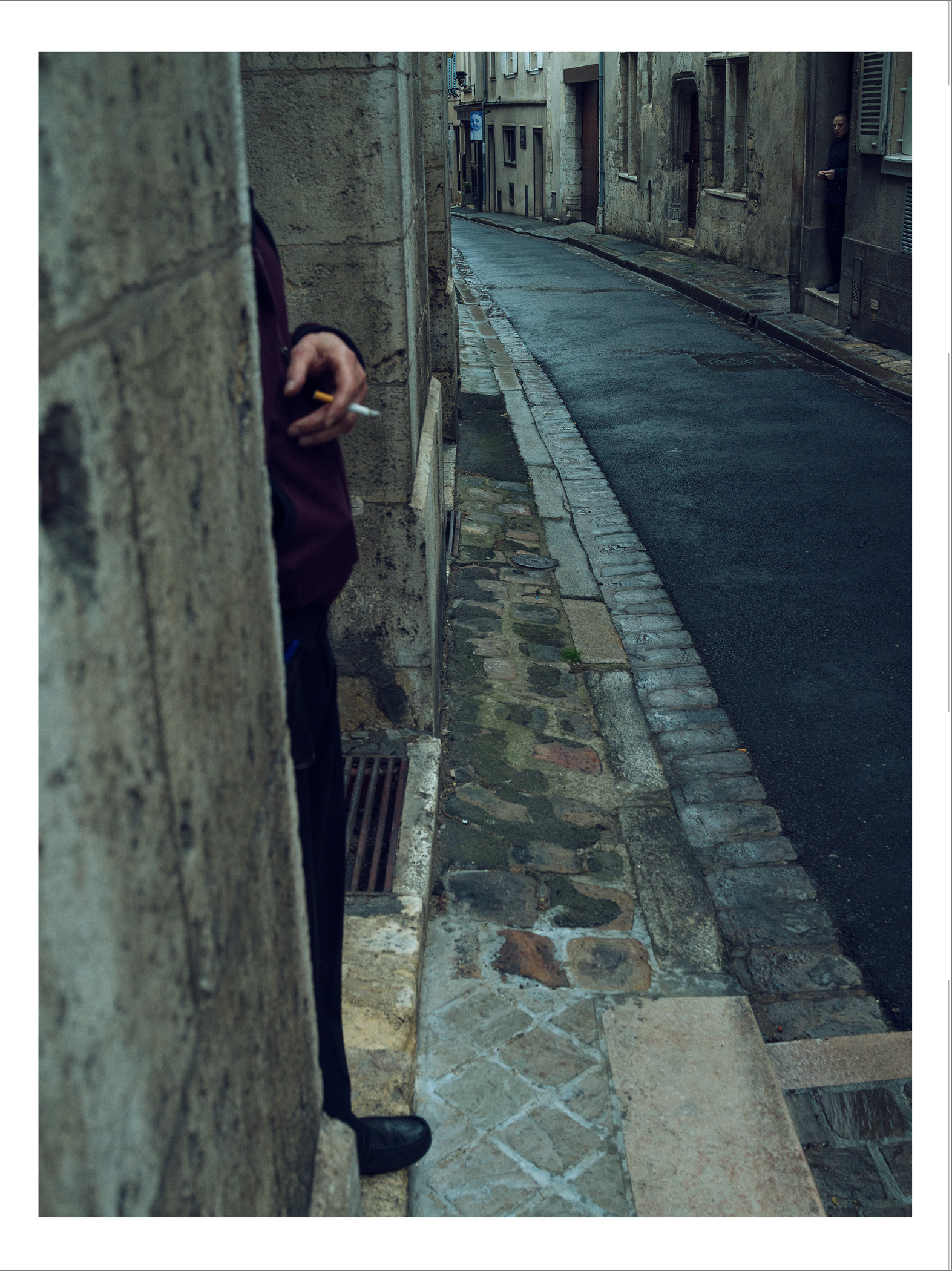

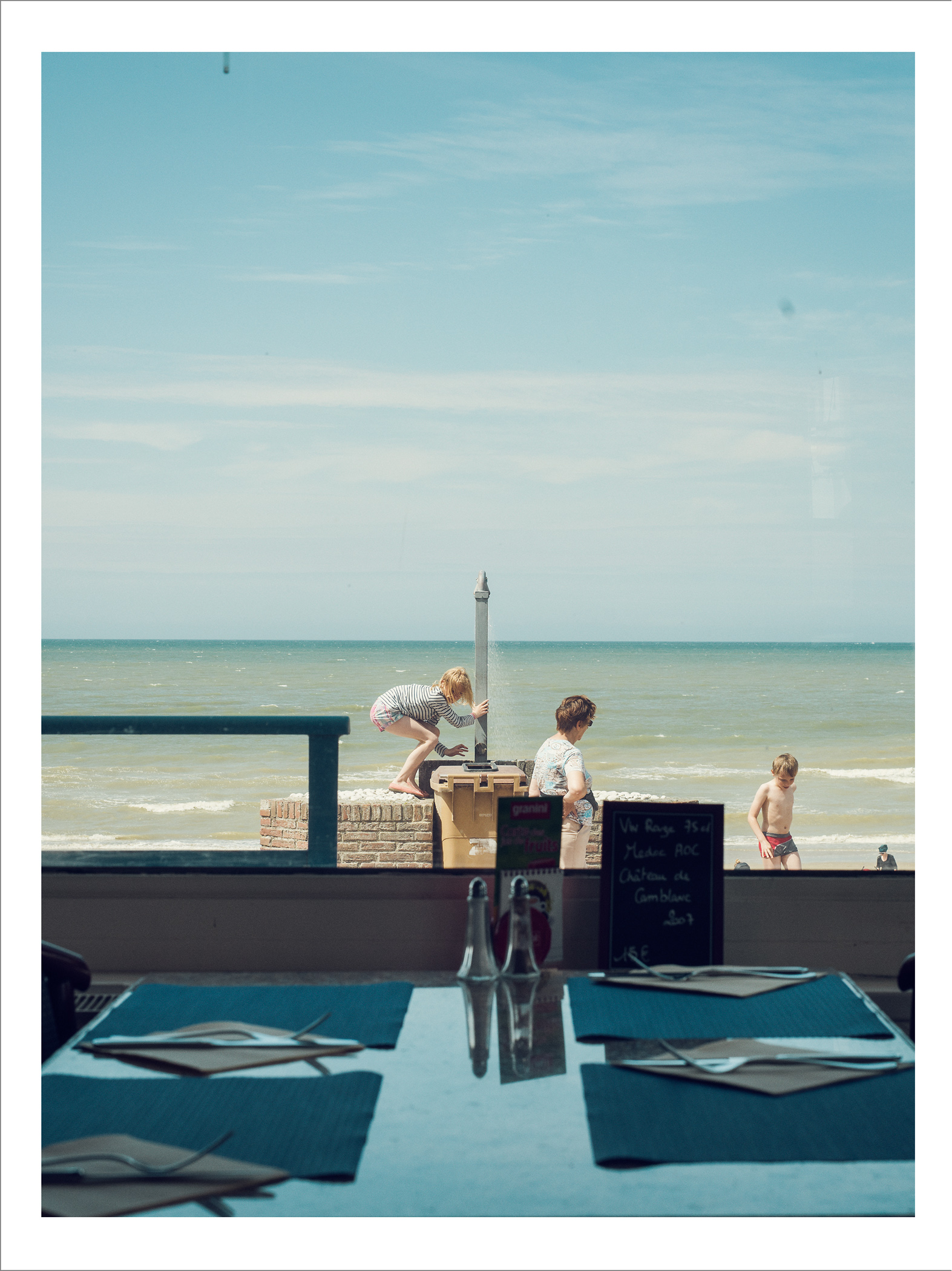

In Bleu, Blanc, Rouge, Anderson’s new body of work, the Canada-born, Texas-raised photographer seeks the colors of the French flag, in an attempt to understand a country that he’s gradually adopting as his own. Married to a French woman, with two half-French children, and in the process of officially becoming French himself, Anderson not only tries to put into photographs his own feelings about France, but also to understand what’s happening in France. “I started noticing the sort of existential crisis that France is going through,” he says. “There’s a cutting edge from a cultural standpoint, but there’s also something that is stuck in another era.”

When he started the work in 2011, having been invited for a residency in Sete, a French city on the Mediterranean coast, Anderson was surprised to see the colors of the French flag celebrated during Saint-Louis, a folklore festival of jousting that has its origins in the Crusades. Though the colors of the American flag were a common sight in Texas, he had been told that things were different in his new nation, that only nationalists displayed the flag and its colors — until that festival, at which the French flag was everywhere. “So I started playing with the colors of the French flag,” he says, “[especially since] a lot of people kept telling me: ‘We French don’t have the same rapport to the flag.’”

Over the last five years, this standard line has changed, he says.

“I feel like [the flag] has been taken back. It’s been taken away from the Front National. Last night, at the celebrations, the flag was everywhere and it didn’t seem like this out-of-place symbol anymore,” the photographer said on Monday. Anderson isn’t sure what happened. “Maybe it’s a mixture of things. While the terrorism that has taken place in the past couple of years has politically divided people in some way, it has also brought them together [to feel] pride about being French and being in an open and free society. There’s something about being part of Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité. You saw that reality in the crowd last night.”

Anderson was also driven by the desire to fill a void he was seeing in French photography. “From a photographic history, it struck me, as I was looking at my pictures, they were the pictures that I’d imagine a French photographer might make about France,” he says. “In American and British photography, there’s a tradition for photographers to look at themselves, maybe in a narcissistic way, with a certain melancholy and a certain critical eye, with a certain distance; with the existential question: who are we?”

In that way, as Anderson embraces that question in his own pursuit of a French identity, Bleu, Blanc, Rouge also continues an introspection he began years ago when he documented the birth and first years of his son, Atlas. “When I made these photographs, I didn’t think they were part of my work at all,” he says. “I thought they were just pictures a father does. Now, I realize that’s really where my work begins.”

Christopher Anderson is a Magnum photographer.

Olivier Laurent is the editor of TIME LightBox. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram @olivierclaurent

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com