Ryan Murphy is taking a rare breather. We’re in his tidy trailer on a set in Hollywood, at the end of the last day of shooting for The Boys in the Band, a play that Murphy revived on Broadway in 2018 and is now producing as a feature film for Netflix. Outside, the studio lot is surprisingly sedate. A golf cart whirs past. A colleague brings him a single shot of espresso. Murphy, 53, schedules his days into short intervals—15 minutes, or 30—and works seven days a week. “I say I can’t keep going at this pace,” he says. “But then I have a full physical, and it’s like, I’m fine.”

For someone with at least 15 projects in the works, he’s unusually hands-on with all of them: writing, directing and producing. He still has two shows on Fox—9-1-1 and an upcoming spin-off—and three on the cable network FX: Pose, American Horror Story and a new installment of American Crime Story, which will follow the Monica Lewinsky scandal. That would be a busy slate for anyone—but this is the peak-content era, where each day seems to bring news of another creator defecting from established studios and networks to streaming services—whether heavyweights like Netflix, Amazon and Hulu or upcoming launches such as Apple TV+, Disney+ and HBO Max—with the promise of capacious budgets and creative freedom. Murphy is, by the numbers, the biggest: last year he departed Fox, his longtime home, for an unprecedented deal with Netflix, valued at $300 million—the most lucrative TV pact in history.

For the streamer, he’s been developing a new roster of projects, at a scale, scope and variety that’s unmatched even in the Wild West of the content boom. He is prepping the Sept. 27 release of The Politician, a sharp, crackling series about an ambitious young man, played by Ben Platt, running for high school office. He’s editing Ratched, a moody origin story about One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’s Nurse Ratched, starring Sarah Paulson. (The show is a disturbing midcentury tone poem set on the California coast, with a scene-stealing supporting performance by Sharon Stone.) He’s adapting two Broadway musicals for the screen: A Chorus Line will unfold as a 10-part miniseries, and The Prom, a feature, will star Meryl Streep and Nicole Kidman. He takes great pleasure in casting, especially when it comes to megawatt movie stars, many of whom he now counts as friends. (“I have everyone’s phone number but Meryl Streep’s,” he says. “There’s everybody, and then there’s Meryl.”)

Hollywood, featuring Patti LuPone and Holland Taylor, will debut in May and “look at Hollywood and the sex industry, and how absolutely everything has changed and nothing has changed.” And he’s making a miniseries about the designer Halston, with Ewan McGregor playing the couturier.

Then there are the documentaries: A Secret Love is about a closeted lesbian couple who came out in their 80s. There’s also a “big, flashy 10-part series” about Andy Warhol, whom people see only as “this sort of queen, so who’s the real person who made all this stuff that changed all of our lives?” And he’s making a docuseries about the most stylish people in the world, because he loved year-end lists as a kid. “Who’s in? Who’s out? Who’s the most?”

Oh, and also: “Jessica Lange and I are working on a piece about Marlene Dietrich in Vegas in the early ’60s,” he says. “But I’m so booked. When am I going to do it? I don’t know.” He sighs and looks momentarily beleaguered. “I’m only into April of next year’s calendar.”

***

Murphy grew up in Indianapolis, in an era—and in a family—where it wasn’t easy to be a gay kid with an artistic sensibility. His father, in particular, was tough on him: “He would ask me, ‘Why aren’t you like me?’” he remembers. “I was constantly in existential crisis about who I was.” Although Murphy reconciled with his father before he died—and has softened now that he has two children of his own, with husband David Miller—that rejection still smarts. “I never got over that,” he says, “and I probably never will.”

Yet it may have ended up fueling his ambition. After moving to Los Angeles, he spent his 20s working as a journalist for outlets like the Miami Herald and the Los Angeles Times where, he says, he would churn out three stories a day, sharpening his work ethic. He sold his first show, Popular, to the WB in 1999 but butted heads with network executives. “I wasn’t allowed to have a gay character,” he says flatly. “They told me that I didn’t understand the tone of it. I was like, ‘It’s my show!’” And although he worked steadily—creating the cult hit Nip/Tuck for FX and adapting and directing best-selling memoirs Running With Scissors and Eat Pray Love as feature films—he didn’t always feel supported. “All the guys in power were straight white men,” he says. “J.J. Abrams and I came up at the same time, but I never got those calls—because you mentor people who act like you and talk like you, and share your points of reference.” That earned him a reputation. “I was seen as a fighter,” he says. “I wouldn’t take no for an answer.” His creative sensibility was provocative and breakneck, marrying satirical elements with earnest drama, which divided critics.

Then came a string of hits, all of which, he says, everyone thought would never work: He created Fox’s prime-time musical Glee in 2009, which—with tours, merchandising and a reality-show spin-off—became an asset worth hundreds of millions of dollars. For FX he dreamed up American Horror Story in 2011, one of the first series to function as an anthology, reimagining the show anew each season. For HBO he directed an adaptation of Larry Kramer’s play The Normal Heart in 2014, which won him an Emmy and earned eight more nominations. And for FX in 2016, he retold the O.J. Simpson saga in American Crime Story, earning the best reviews of his career. “After those four things,” he says, “it was like, Whatever you want to do, you can do.”

In his newfound seat of power, he realized he’d derived the most fulfillment from working with people who hadn’t traditionally been in the spotlight—whether that was actresses of a certain age or trans women of color—and decided to double down on this as his ethos. “Everything I’m working on is about one idea—taking marginalized characters and putting them in the leading story,” he says. Dana Walden, now head of Disney Television and ABC, championed his work at Fox for this very reason. “Ryan tells stories about outsiders, but his shows are so commercial and shiny,” she says. “I cannot tell you what a hard needle that is to thread.”

His efforts have coincided with a larger movement to make Hollywood a more equitable, safe and inclusive place. This has been spurred on by two big reckonings: the first, around sexual misconduct and gender discrimination, and the second, a call for diversity in front of and behind the camera. “The thing that I had been peddling suddenly became very desirable,” he says. But his investment in inclusion isn’t cynical: it’s rooted in his own pain, this desire to become the head of his own makeshift family. “I’m being the father who says, ‘You’re enough,’ which no one ever said to me,” he says. “I’ll spend hours in negotiations to get actors—especially women and minorities—more money than they’ve ever had.” Case in point: his collaborator Janet Mock, who wrote, produced and directed episodes of Pose, recently signed a multimillion-dollar deal with Netflix, making her the first trans woman with an overall pact at a major media company. “He puts a lot of wind beneath the wings of the people he believes in,” says Paulson. “I don’t think anyone ever did that for Ryan.”

By bolstering his colleagues, Murphy also benefits—he’s built a community of colleagues who are fiercely loyal to him. Yet he’s still driven by his need to belong and to be valued by the Establishment. “My whole life has been in search of that brass ring, and now somebody actually thinks I’m worthy as opposed to being an aberration?” he says. “People are astounded that I still want that. But everyone wants to be seen. Everyone wants to be loved.”

***

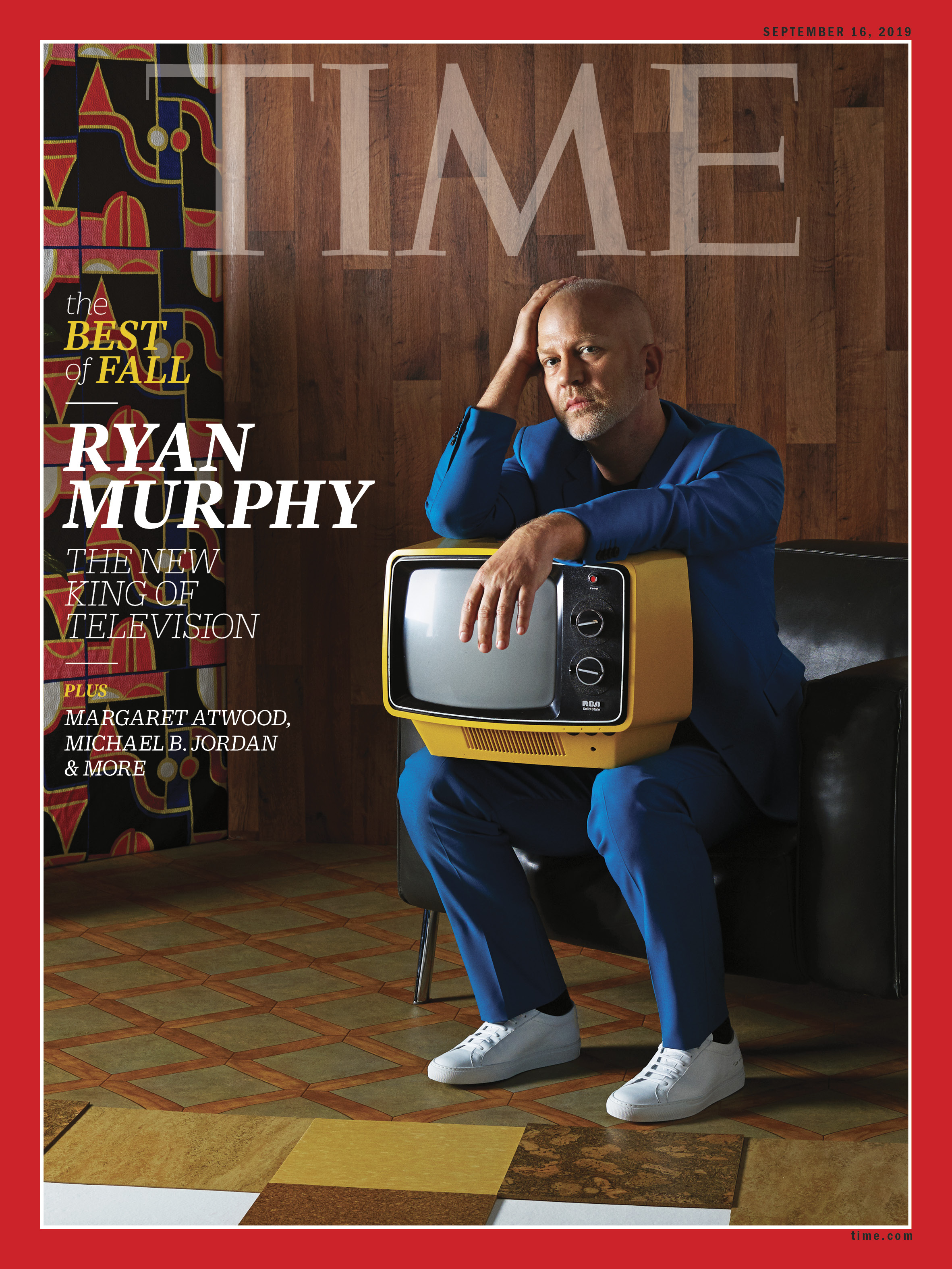

A few days later, at a photo shoot in Culver City, Murphy stands before shelves lined with two dozen hats a stylist has pulled: wide-brimmed chapeaus in rose and silver, lilac and camel. He ends up not wearing any of them.

But glamorous excess still reigns, both in his life and on The Politician, his first show for Netflix, which might be the Ryan Murphiest show Ryan Murphy has ever made. You want shocking violence, Machiavellian teens, withering one-liners, Gwyneth Paltrow having an affair with a horse trainer played by Martina Navratilova, musical numbers, Munchausen syndrome by proxy, and Jessica Lange in gold lamé? That might sound like a lot. But it’s also calibrated for a mass audience—because Murphy’s sensibility has become the sensibility of the mainstream.

“His work is a reflection of his own interests and sensibilities, but it’s broader than that,” says Cindy Holland, who runs original programming at Netflix. “He’s absorbing influences in pop culture to create these unique collages that appeal to many different groups.” Critics have rallied behind some of his projects while dinging others, but he challenges the narrative that certain shows, like his Emmy-sweeping opus The People v. O.J. Simpson, are more restrained on purpose. “That show is outrageous!” he says. “John Travolta’s eyebrows are outrageous! There was a whole makeover episode! I never change.”

If he is too much, it has proved to be an asset—too much is exactly what people want. “Call me camp,” Murphy says. “Call me crazy. Call me wild. Call me extreme. Call me erratic. The one thing you can’t say is that I don’t try.” He thinks about it for a second and smiles wickedly. “Actually, I don’t care what you call me,” he says. “As long as you call me.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com