Apple’s latest announced changes to how it’s handling both children’s privacy and illegal material have stirred up controversy around encryption and the right to privacy. But chances are you’ll never notice a change to your daily texting and photo taking.

On Friday, Apple announced new changes to how it handles certain images in its iCloud Photo Library, as well as certain images sent via the Messages app. The implementation is set to arrive later this year with the delivery of iOS 15. While the changes, designed to protect children from abusive and sexually explicit material, are part of a larger fight against child abuse content, the company’s implementation has left many claiming the company is compromising its high standard of encryption. Confronted with questions, Apple has spent the week explaining its newest changes to how it scans iCloud Photos as well as images sent to minors in Messages on iOS.

What did Apple announce?

Apple’s new Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM) detection tool will begin scanning photos users upload to their iCloud Photo Library for child abuse material, and will lock users out should multiple images be detected. It’s also adding an image scanning tool for minors in Messages, so both children and parents can be aware of when they’re viewing explicit imagery.

More from TIME

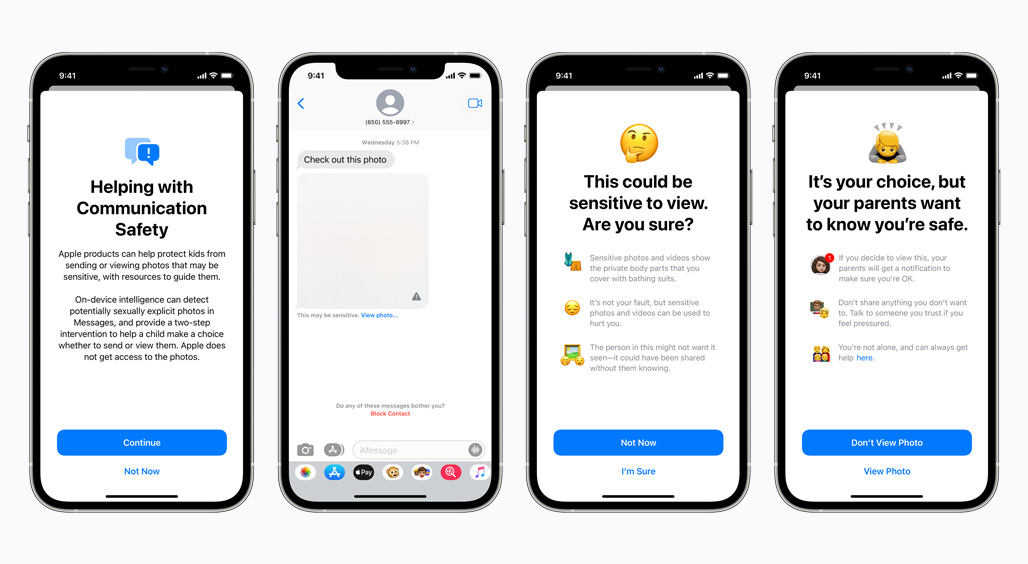

The Messages feature, designed for minors, will alert parents when sexually explicit imagery is being shared, warning the minor not to view the content, and alerting the parent should they decide to look. Apple says the image scanning tool was trained on pornography, and can detect sexually explicit content.

Parents must opt in to the communication safety feature in Messages, and will be notified if an explicit image is opened if the child is 12 years or younger. Children age 13 through 17 will still receive a warning when opening an image, but their parents will not receive a notification should the image be opened.

Apple’s new set of child safety features, made by collaborating with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), seeks to protect children from abusive activity and sexual imagery. On the surface, it might seem as though Apple is compromising its intended goal of increased user privacy for the purpose of monitoring photos, and some experts agree. But the company is far from the first to scan user generated activity for Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM).

Both Apple’s CSAM detection tool for iCloud Photos and the new explicit image scanning tool for minors is considered invasive by privacy advocates and cybersecurity experts. Some see it as a step toward the erosion of true data encryption and privacy, where access to a user’s image library in any way can be used by governments willing to pressure Apple into playing along. According to a New York Times report, Apple has already allowed Chinese state employees to run its servers, which store personal data for Chinese iOS users.

The new tools also seemingly run counter to Apple’s strong stance on privacy and denying access to user data requests by law enforcement.

How will Apple’s image detection work?

On its “Child Safety” page, Apple details the privacy changes coming to iOS and iPadOS. It says that the photo detection will primarily be used to deal with inappropriate imagery and abusive material. New image-scanning software will be loaded onto iOS that will scan photos uploaded to iCloud Photos for CSAM.

Apple says the tool will scan the images before they’re uploaded to iCloud Photos and compare them to its database of known CSAM image IDs with unique fingerprints (also called “hashes”). They point out that it will compare unique image hashes, and not the images themselves.

Apple says it can only take action when it discovers a “collection” of known CSAM imagery after they’ve been uploaded to your iCloud Photo Library. When a collection “threshold” has been reached, Apple says it will manually verify the contents of the images and report the images to NCMEC while locking the user out of their Apple ID. Apple says the chances a user will be marked as a false positive are one in one trillion.

Will Apple look at your photos?

Apple says it is not looking at photos themselves, so there is no chance of someone getting a glimpse of any actual images, unless they are submitted for human review after meeting certain requirements. Both the NCMEC database and the flagged images in question cannot be viewed by Apple, nor can any human view the flagged images until the user’s collection of CSAM reaches a certain “threshold” of images.

Apple will not scan photos sent and received in the Messages app for CSAM, only those uploaded to iCloud Photos (photos in Messages to minors participating in the safety feature will be scanned for sexual imagery). Only photos included in the database will be flagged, and no CSAM not found in the database will be classified as such.

Also, Apple says in its FAQ concerning the expanded protections that “Apple will not learn anything about other data stored solely on device.”

In the FAQ, Apple says it has no intention of allowing governments or law enforcement agencies to take advantage of this image scanning tool: “We have faced demands to build and deploy government-mandated changes that degrade the privacy of users before, and have steadfastly refused those demands.”

Since all the processing is done on the device, Apple says there’s no compromise to the company’s end-to-end encryption system, and users are still secure from eavesdropping. But the idea of scanning images for inappropriate imagery already creates a chilling effect, with the idea that a conversation is, in a way, being monitored.

Can you opt out?

While every iOS device will have these tools, that doesn’t mean every device will be subject to its image comparisons. You can disable uploading your photos to iCloud Photos if you don’t want Apple to scan your images. Unfortunately, that’s a huge hurdle, as iCloud Photos is, well, pretty popular, and a key feature in Apple’s iCloud service as a whole.

As for the communication safety in Messages feature, once opted in, the new image scanning tool only works when communicating with a user under the age of 18 on an Apple Family shared account.

Why is Apple doing this now?

Apple claims it’s implementing this policy now due to the new tools’ effectiveness at both detecting CSAM as well as keeping users’ data as private as possible. CSAM detection happens on the device, meaning Apple can’t see any images, even CSAM, until multiple instances have been detected. Apple’s image scanning feature should never reveal any non-CSAM imagery to Apple, according to the company.

The company isn’t the first to scan for this sort of content: companies like Facebook, Google, and YouTube have CSAM policies as well, that scan all uploaded images and videos for similar activity using a similar “hash” technology that compares it to a known database of CSAM.

Many privacy advocates and organizations are raising concerns when it comes to scanning user photos and Apple’s commitment to privacy, despite the good intentions. Critics think any software that scans encrypted user-generated data has the potential to be abused.

And critics to Apple’s latest change have a trove of evidence backing them up. The Electronic Frontier Foundation, in a statement, claims there’s no safe way to build such a system without compromising user security, and points out that similar image scanning services have been repurposed to scan for terrorist-related imagery with little oversight.

“Make no mistake: this is a decrease in privacy for all iCloud Photos users, not an improvement,” says the pro-privacy organization in a statement criticizing the new feature.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Patrick Lucas Austin at patrick.austin@time.com