When Jennette McCurdy lost her mother to breast cancer in 2013, she went to therapy: “Really, really intense therapy,” she says. It’s not hard to understand why: From the actor’s earliest memories, her mother, Debra McCurdy, had been abusive, pushing her into a demoralizing career in the entertainment industry and encouraging her anorexia, among myriad other forms of trauma. McCurdy had become a star on Nickelodeon, appearing on the hit show iCarly and Ariana Grande two-hander Sam & Cat, and launched a country music career, but as she walked away from the Hollywood machine in the wake of her mother’s death and began to work on herself, she came to grips with how badly she needed to tell her own story. “I felt compelled to do it,” McCurdy says. “I couldn’t think about anything else until I got it out.”

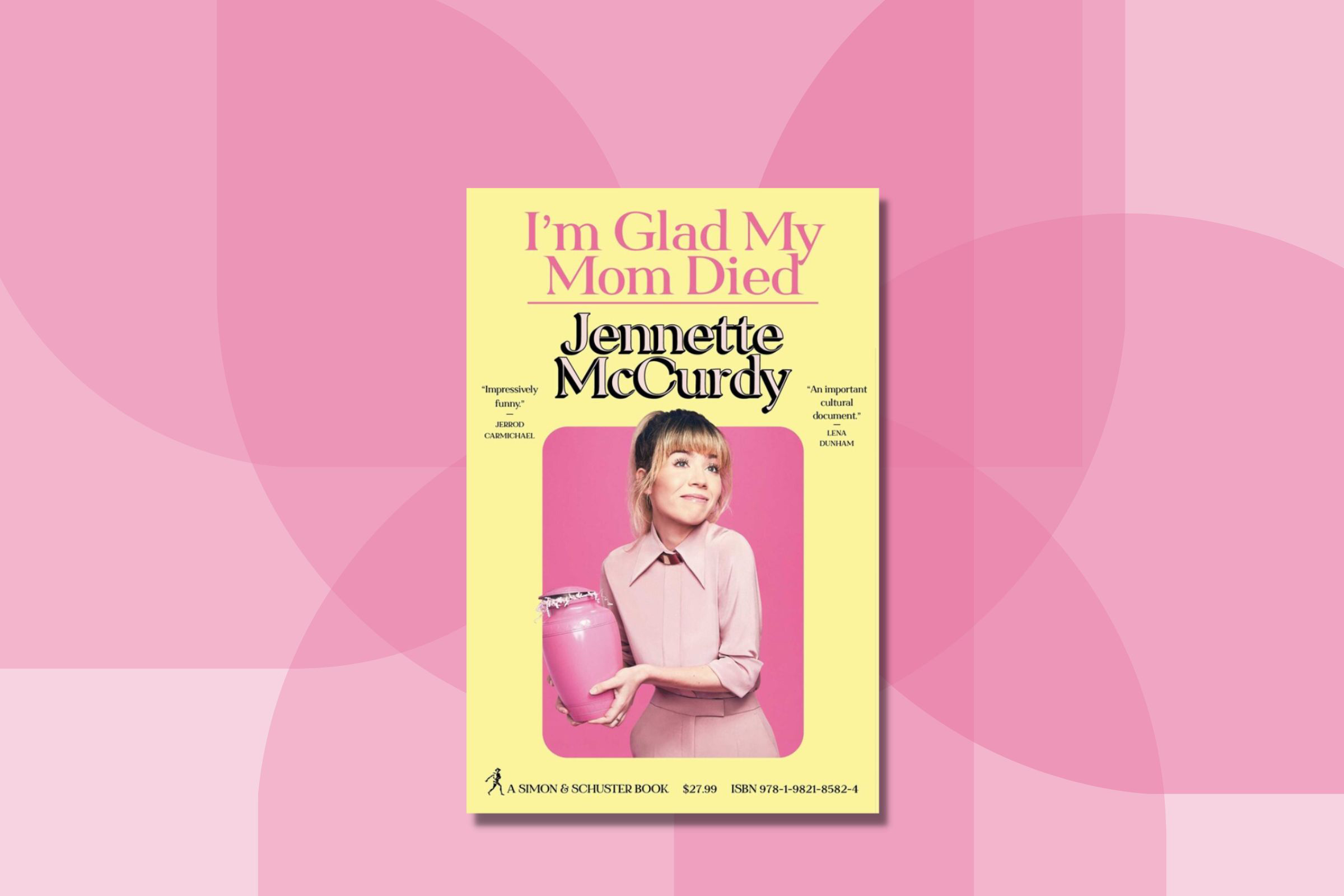

After first performing a one-woman show called I’m Glad My Mom Died, McCurdy, now 30, wrote a memoir by the same name. With the book, to be published Aug. 9, she reveals herself to be a stingingly funny and insightful writer, capable of great empathy and a brutal punchline. It’s a document not just of all she’s endured, but also of the wisdom she accrued along the way.

In conversation with TIME, she reveals how she became ready to write it.

TIME: Before you wrote this book, you were performing a one-woman show with this same title. How are they different?

McCurdy: The material is overlapping: They’re both autobiographical and both my life, and they have the same name. But I see them as two separate projects. The live show was designed specifically for an audience, and it’s a musical. It delves into the three years after her death where I struggled the most. The book covers my childhood more, and my Mormon upbringing, and experiences as a child actor.

Was there a critical juncture where it felt like it was time to write the book?

Because it’s so personal, I felt like it was important that I had a lot of experience in therapy. I didn’t sit down with a therapist and say: “So I want to write a memoir. How can we get me to a place where I’ve got the perspective to do it?” But it was several years of really intense therapy before I started feeling like I could explore all that personal stuff creatively.

How do you feel about Hollywood now, having had such difficult experiences in the child-star assembly line?

There’s complicated, layered gratitude. This is so corny, but I mean it genuinely—I think of Hollywood less as a domineering force, and more about the people in Hollywood that you surround yourself with. The people who I’m surrounded by now have restored my faith in it.

Do you feel like you’ve recovered from what you’ve went through? When I think about my own recovery, sometimes I feel healed, and sometimes I feel like I’m just performing being healed.

My mind just went: Is it possible to be so full of sh-t that you can’t see when you’re full of sh-t? And then I was like: No, I think I’ve done too much therapy for that. I consider myself fully recovered from eating disorders, and I’m really, really proud of that. And yet, I think that elements of my relationship with my mom will always be something that I’m exploring in some way, whether that’s just subconsciously kicking around or whether that’s creatively. But I don’t think that’s a bad thing. It doesn’t feel re-traumatizing for me to explore that relationship creatively.

There’s so much pain in this book, but you write about it with such grace and humor. What were the influences that helped you develop that?

My relationship with my brothers has been a great source of camaraderie and support for me. My grandfather provided me a lot of love and support. And, weirdly, entertainment. Movies, books, and shows can provide a lot of comfort and solace. That’s especially important for people who grew up in dysfunctional or lonely environments.

Were there books that you read in the process of writing your own that were touchstones for you?

I struggle with books about writing, but I loved Jeannette Walls’ memoir The Glass Castle. She does such an incredible job of weaving in humor, and telling it so colorfully but so plainly.

Let’s say your book gets turned into a show, and there’s a 7-year-old actor who’s going to play young you. What advice would you give her?

First off, I would make sure that the set hires a child psychologist to be present for her. But I would also talk to her like she’s a person, while also respecting that she’s a child. In my experience as a child actor, people either talked to you like you’re dumber than you are, or they talked to you like you’re an adult. Neither of those are as respectful as kids deserve. My hope would be that any child actor doesn’t lose their—this term is so overused but—authentic self. That’s the thing that gets rattled if you lose sight of it: who you are underneath the characters and lights and red carpets.

When all that stuff went away, what were the things you found about yourself that surprised you?

Naturally, by being in the public eye at a young age, you have so many opinions around you. The most potent for me was my mom’s opinion, which was so in my ear that I couldn’t identify what I wanted or even needed at any given moment. So I had to step away completely. I quit acting. I wasn’t on social media for years. I was dedicated to recovery. That was when I started to be able to connect with myself and identify what I wanted and needed. It sounds basic, but it was really a struggle for me.

Do you think Hollywood is changing with respect to body positivity? I thought your book peeled back the veneer on diet culture in the entertainment industry in a way that was unusual.

I don’t blame anyone for any of their comments that reinforced my disordered eating if they had good intentions and just thought they were saying something nice. But there were a lot of comments that made me uncomfortable.

Beyond the specifics of what you went through, do you think it’s still a problem more endemically?

The best path for me has always been to work on myself personally, and then I feel like I’m able to brave whatever “society” throws at me. So my hope is that people continue to prioritize their own mental health and continue doing that work. It’s something each person has control over.

It sounds like you have good boundaries.

I don’t think people talk about boundaries enough. I remember sitting in therapy and I kept hearing the phrase. I was like, What are these boundaries that people keep talking about? I didn’t know how to implement one. There was a lot of trial and error in learning to do boundaries in a graceful way.

Will you write more books?

I’m working on a novel and a collection of essays now. They just came one after the other. It’s been nice to have two projects at the same time, so I’m avoiding burnout on both of them.

How does it feel now, on the precipice of releasing your memoir?

I spent six years of time, effort, and energy on the things that I explore in this book, but in a completely unpresentable way. That work got me to the place where I was able to start exploring it creatively. So ultimately, what wound up on the page, that’s all stuff that I really believe in and stand by. So I feel confident. I feel ready.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com